The exhibition The Power and Pleasure of Possessions in Korean Painted Screens explores the genre of Korean still-life painting known as chaekgeori 冊巨里 (loosely translated as books and things). Chaekgeori [Check-oh-ree, 책거리) was one of the most prolific art forms of Korea’s Joseon dynasty (1392–1910), and it continues to be used today. It often depicts books and other material commodities as symbolic embodiments of knowledge, power, and social reform.

For the first time in United States, more than twenty screen paintings dating from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries of the Joseon dynasty are on view at the Charles B. Wang Center at Stony Brook University in New York from September 29 to December 23, 2016.

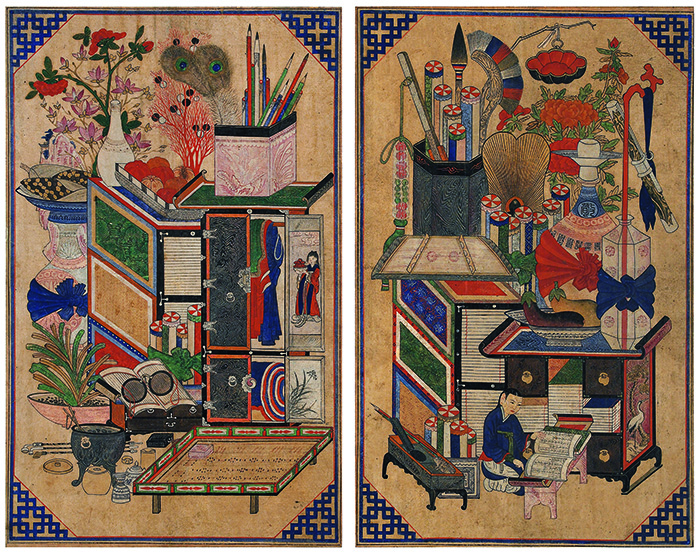

Chaekgeori, the Scholar’s Accoutrements. Late nineteenth-century Korea. Ink and color on paper, Ten-panel screen, 78″ (H) x 152″ (W). Private Collection.

Curated by a group of Korean art experts that includes Byungmo Chung (professor, Gyeongju University), Sunglim Kim (professor, Dartmouth College), Jinyoung Jin(Director of Cultural Programs, Charles B. Wang Center), Sooa Im McCormick (Assistant Curator of Asian Art, Cleveland Museum of Art), and Kris Imants Ercums (Curator of Global Contemporary and Asian Art, Spencer Museum of Art), this collection showcases marvelous and rare examples of chaekgeori screens alongside the works of a diverse body of contemporary artists who continue this genre into the twenty-first century. Seven contemporary artists featured in the exhibition are Stephanie S. Lee, Seongmin Ahn, Kyoungtack Hong, Patrick Hughes, Sungpa, Young-Shik Kim, and Airan Kang.

Initially intended as a means to maintain and promote the disciplined Confucian lifestyle of Joseon Korea against an influx of ideas and technology from abroad, King Jeongjo (1752–1800, r. 1776–1800) encouraged court painters to emphasize books as the main subjects of royal screen paintings and to embrace the power of books and the ideas contained within them. He even went so far as to replace the screen behind his throne with a new chaekgeori screen—an extraordinarily dramatic break from tradition at that time. Realizing that books were vehicles of change in his society, King Jeongjo worked hard to popularize the idea of books as symbols able to transcend the tangible originals among Korea’s artisans and other elites. Yet in process, the value of physical books actually increased, and books were highly sought-after. This desire for books and other commodities in Korea set in motion a significant social and cultural shift toward materialism that continues into the twenty-first century. One can say that chaekgeori paintings not only have the ability to teach and inspire, but they also possess the power to shape the values of a society.

– by Jinyoung Jin, Director of Cultural Programs at the Charles B. Wang Center, Stony Brook University

After its run at the Charles B. Wang Center, the exhibition will travel to the Spencer Museum of Art at the University of Kansas (April 8–June 12, 2017), and then to the Cleveland Museum of Art (August 5–November 5, 2017). An exhibition catalogue will be available soon.

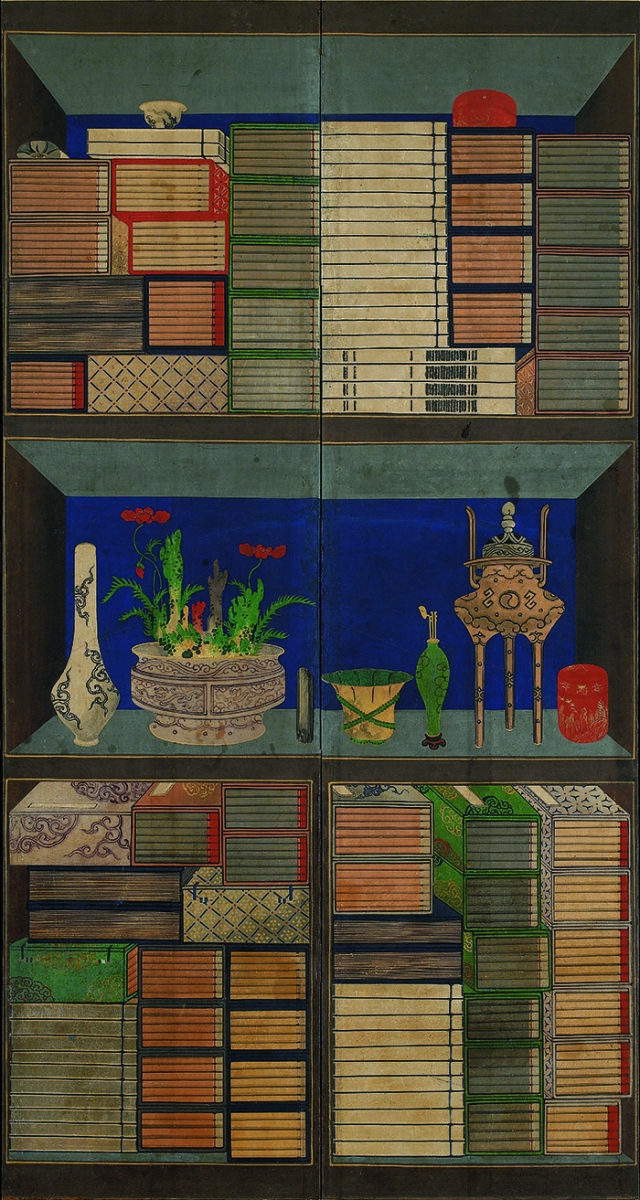

Chaekgeori, the Scholar’s Accoutrements. Late nineteenth-century Korea. Ink and color on paper. Six-panel screen, 59″ (H) x 114″ (W). Private Collection.

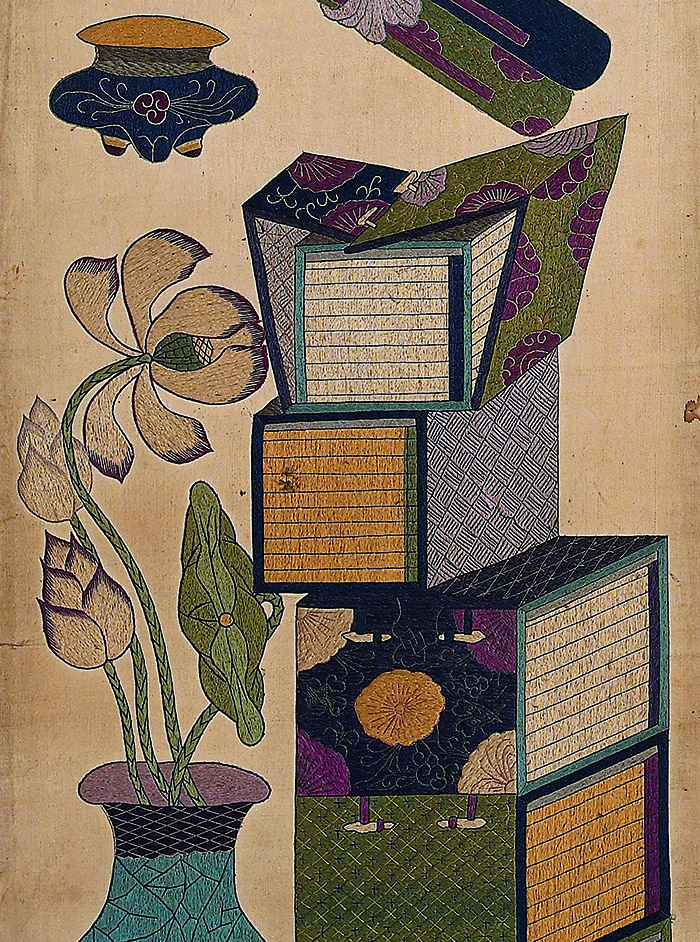

Stephanie S. Lee. Cabinet of Desire II, 2016. Natural mineral pigment, colored and gold pigment, ink on Korean mulberry paper. 48″ (H) x 50″ (W) x 2”(D). Courtesy of the Artist.