Kitagawa Utamaro, Wakaume of the Tamaya in Edo-machi itchome, kamuro Mumeno and Iroka, ca. 1793-94 (Edo-machi itchome, Tamaya uchi Wakaume Mumeno Iroka), with mica ground, signed UTamaro hitsu with censor's eal kiwame (approved), with a kyoka, and publisher's mark of Tsuaya Juzaburo, ca. 1793-94, oban tate-e 14 1/2 by 9 5/8 in., 36.8 by 24.6 cm.

Two of our dealer participants are exhibiting in the IFPDA Fine Art Print Fair online exclusive, which runs until November 1.

In addition to Japanese print classics, such as Harunobu, Hiroshige, Utamaro and Hasui, Scholten Japanese Art is featuring several prints from their September show, “Composing Beauty,” an exhibition exploring ways in which bijin (lit. 'beautiful person') are presented in ukiyo-e.

The courtesan is Wakaume of the zashiki-mochi ('having her own suite') rank of the Tamaya house owned by Tamaya Hayachi.

In about 1792-1793, the publisher Tsutaya Juzaburo (1750-1797) began producing print series by Utamaro depicting half-length portraits of beauties with glittering full-mica backgrounds. These lavish images elevated print production to new heights, establishing both Utamaro and Tsutaya as pre-eminent ukiyo-e artist and publisher, respectively.

This print is from a group of three which were likely intended as an informal triptych, each featuring a courtesan identified in the title cartouche with her house and naming her two kamuro with an accompanying kyoka poem. Of the three designs, this composition functions best at the central panel because the figure's body faces one way while she turns to look in the opposite direction, and one of her kamuro peeks out from behind in a rare instance of frontal portraiture.

Ito Shinsui (1898-1972), Haru (Spring), 1917

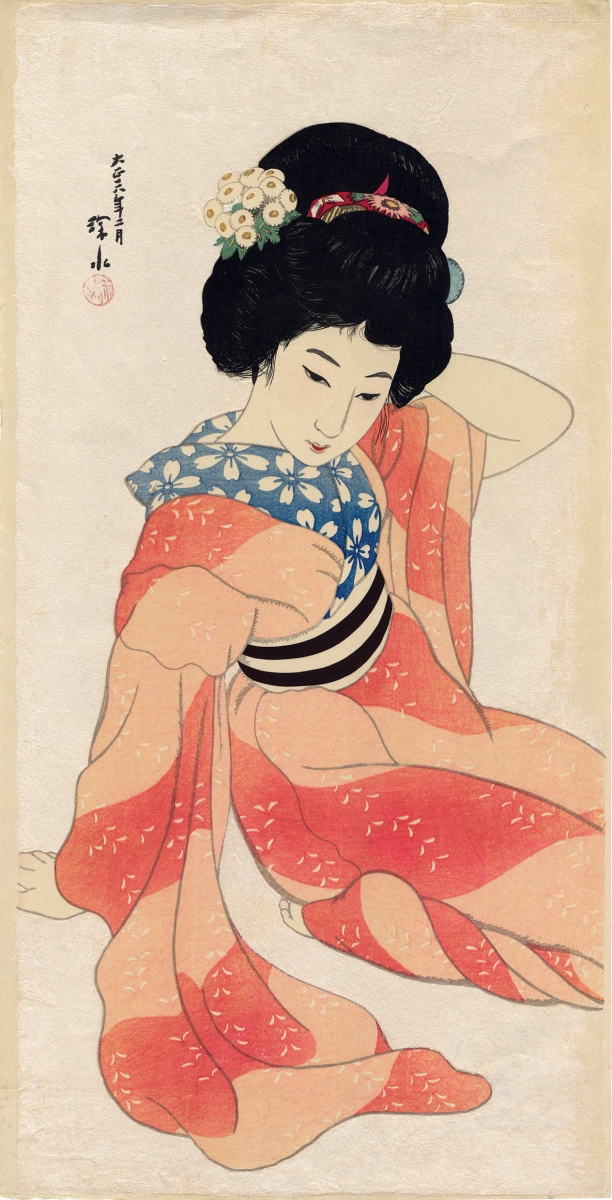

Kitano Tsunetomi (1880-1947), Maiko (Apprentice Geisha in Kyoto), 1925

Very scarce design of a young geisha (known as a maiko) shown in profile. Her face is an opaque white, set against a soft pink/silver mica background. Her hair appears as if painted with a brush, and includes strands of pink and red, as well as a number of youthful ornaments. Her neck is exposed and we can see the tie-dye technique of her robe. The pigments and printing style are unusual for a work from this period. The edition information is in the bottom margin; this is number 12 out of a limited edition of 100 prints. Oversized. Tsunetomi is primarily known as a nihonga painter, and he only published 11 prints, all of them based on paintings.

The Art of Japan, a participant in the New York Satellite Print Fair on until October 25, is presenting a wide ranging group of prints by renowned artists including figural works by Utamaro and Kunisada as well as landscapes by Hiroshige and Hasui.

Hiroshige (1797-1858), Kameido Plum Garden, 1857; from the seires: 100 Views of Edo, 14.375 x 9.75 inches, Woodblock Print Fine impression, color and condition

Even if you are not familiar with Japanese prints, there are a few designs that permeate our visual culture so much that they are icons recognized by nearly everyone interested in graphic art. Hiroshige’s two most memorable images include designs from the famous 1850’s series One Hundred Views of Edo. The first among these quite well known prints is commonly known as Sudden Shower over Shin Ohashi Bridge and Atake, depicting travelers caught in a surprise downpour while crossing a wooden bridge. The second design, one so revolutionary and striking that it also caught the eye of Vincent Van Gogh, is from the same series and commonly known as Kameido Plum Garden, depicting the “Sleeping Dragon Plum” of Kameido. Van Gogh painted a copy of this print in oils in 1877, and you can see the painting on permanent display at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam.

This tree, at the time was the most famous in Edo, and was known for the purity of its double blossoms. According to one Edo guidebook, were “Blossoms so white when full in bloom as to drive off the darkness.” We are so close that we can almost smell the tree's powerful fragrance, reputed to have lured the shogun Yoshimune as he passed nearby in the early eighteenth century. The “Sleeping Dragon Plum” survived in Kameido until 1910 when it was killed by a great flood. (Catalog notes from Brooklyn Museum website)