by Sarah Laursen, Curator of Asian Art, Middlebury College Museum of Art

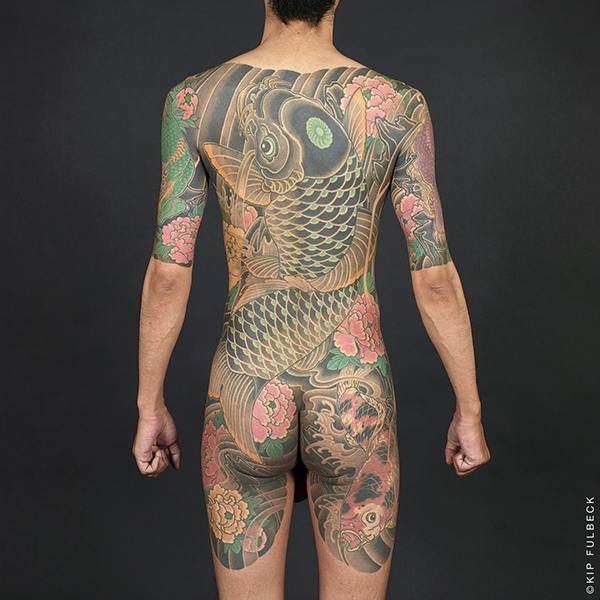

I first encountered “Perseverance: Japanese Tattoo Tradition in a Modern World” two years ago while visiting the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles. Curated by tattoo artist Takahiro Kitamura (AKA Ryūdaibori, formerly Horitaka) and designed by photographer/filmmaker Kip Fulbeck, the exhibition consisted of more than 100 stunning photographs of Japanese-style tattoos, ranging from single sleeves to full bodysuits. I knew immediately that I wanted the exhibition to travel to the Middlebury College Museum of Art in Middlebury, Vermont.

In this exhibition I saw an opportunity to reach out to a diverse cross-section of tattooed Vermonters, including some who may never have visited our museum before. According to The Harris Poll, almost one in three adults in the United States has one or more tattoos, and I suspected that the number might even be higher in Vermont. Even those without tattoos, like myself, might be curious or find inspiration in the gorgeous flowers, fish, deities, and warriors who adorn the subjects of Fulbeck’s photographs. However, in a state with such a small population, I knew it would be difficult to get the word out—I needed a special event to capture the public’s attention.

My brother-in-law, Christopher Holt, and his San Francisco-based tattooer NaKona MacDonald bravely volunteered to do a live tattooing demonstration. Although traditional Japanese tattoo, or irezumi, is performed manually by impressing needles attached to a tool into the skin, this demonstration would employ the tattoo machine, which was invented in 1891 by tattoo artist Samuel O’Reilly.

The only potential obstacle was Vermont’s strict regulatory laws. In order to receive a temporary license—in fact, the first temporary license ever issued by the state—I had to convert the café in the Mahaney Center for the Arts (where the museum is housed) into an actual tattoo shop. This endeavor entailed the participation of more than forty people, including the state inspector who walked me through the process, a local masseuse who lent a massage table, the facilities crew who removed the café’s cappuccino machine, the college lawyers who gave the go-ahead, and the student health center staff who contributed hospital-grade disinfectant and needle disposal. I myself had to draft consent forms and make several trips to the store for gauze, razors, gloves, and other provisions.

On July 9th, with licenses issued, NaKona began sketching out the next phase of Chris’ dragon back piece. That week, a Burlington-based newspaper called Seven Days had listed the event as its top pick for that weekend in Vermont, and more than 300 visitors attended the demonstration and exhibition. (On an average summer Saturday, that number is usually closer to forty.) Museum-goers of all ages—from children perched on parents’ shoulders to octogenarians from the nearby retirement center—flocked to the exhibition and to the café-turned-tattoo-shop, where they peppered NaKona with questions and offered encouragement to Chris.

Perhaps the most remarkable outcome of the demonstration and exhibition was the visible transformation of visitors, from curious and apprehensive to comfortable and inquisitive. Tattooing is still considered taboo in Japan, and that stigma does exist to a lesser degree in the United States. However, exhibitions like “Perseverance” challenge those negative views and open the door to endless new forms of artistic expression.

Watch a brief video of the tattooing demonstration below: