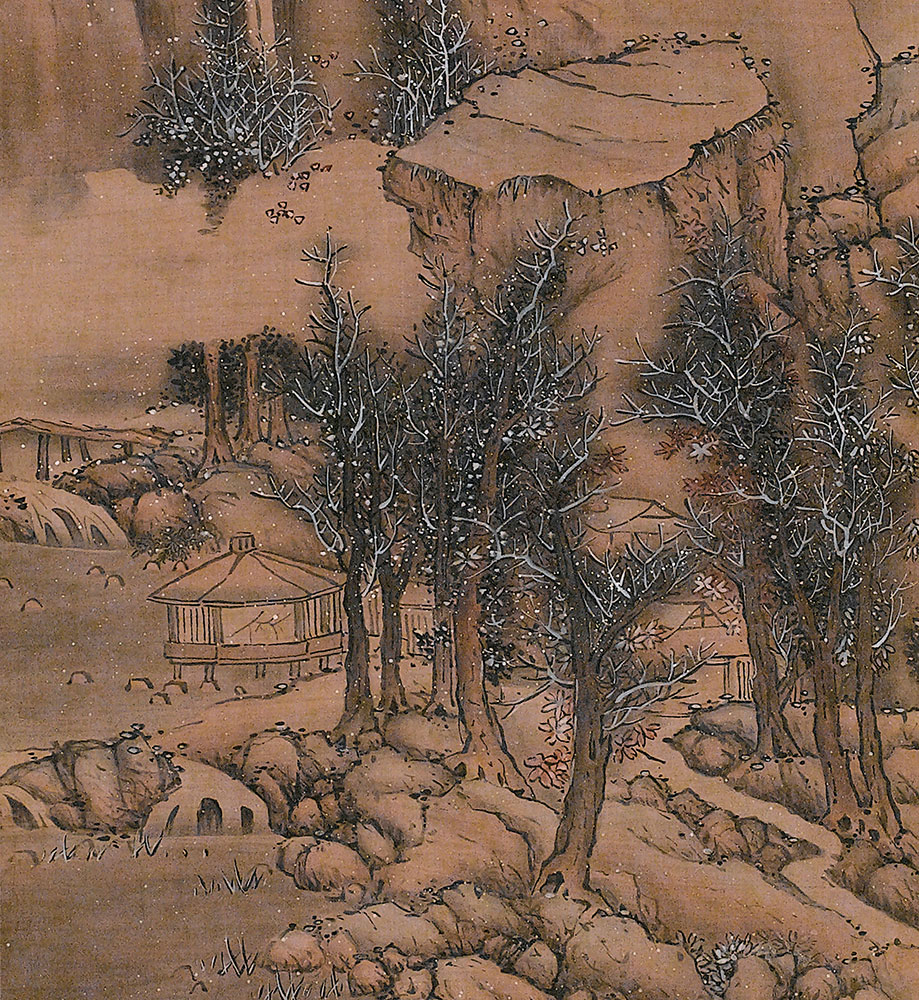

Korean gilt copper “medicine” Buddha, late 7th-early 8th century

We are pleased to share the third installment of additional material related to our recent webinar on art conservation which featured scholarly contributions from two leading Asian Art conservators, Leslie Gat, (Art Conservation Group) and John Twilley (Art Conservation Scientist), along with AWNY members Mary Ann Rogers (Kaikodo LLC), and Thomas Murray (Thomas Murray Asian and Tribal Art).

Part three begins with a summary from John Twilley, followed by answers to questions posed by attendees during and after the event.

“Scientific analysis applied to artworks serves several purposes, chiefly to guide conservation treatment and to inform art history on the physical aspects of the making of art. Cleaning and corrosion removal are operations that frequently entail irreversible changes to an artwork and therefore often require testing to determine their feasibility and impact on the object. As in medicine, the first priority of conservation should be to do no harm. Historically, many attempts to clean and “restore” artworks have been marred by misunderstandings about their materials and original appearance, or by the prioritization, in the imaginations of collectors, of certain characteristics over others that were essential to the artist’s original work. The example of the cleaning and recarving of Greek and Roman sculptures that occurred in the 18th and 19th centuries, during which polychrome decoration was often lost, provides a cautionary tale for how we should approach Asian art. The Victorian preference for white marble surfaces as aesthetically desirable, coupled with an antihistorical denigration of the role of color in the ancient world, allowed much to be lost forever.

Chinese sculptures in wood and stone are widely appreciated to have been decorated with polychrome. What is less often understood is that they were subject to multiple devotional redecorations during their existence in worship and that common practice was to cover the earlier layers rather than remove them. Unfortunately, Chinese sculptures with damaged polychrome decoration have sometimes been stripped of paint remnants in a quest to elevate sculptural form and uniformity. When they have not been removed, scientific study of these successive paint layers allows us to understand the chronology of costume styles preserved there and to date them.

Even less recognized are metal sculptures that were decorated with painted polychromy augmenting gilt bronze. Two sculptures dating to the 8th century CE illustrate the essential role of scientific testing in recognizing the presence of polychrome and preventing its destruction. Testing of a corrosion-covered, late Sui or early Tang bronze Avalokiteshvara revealed painted linework and shading over gold that have become inextricably bound with corrosion products from the bronze and incrusting minerals acquired from the environment. Testing of a Korean gilt copper “medicine” Buddha, which radiocarbon dating confirmed to be of the late 7th to early 8th century, reveals decoration with opaque aquamarine glass and rock crystal “jewels,” the latter of which derived their color from painted settings, contrasting with painted flowers. The peculiar yellow hair of this Buddha, which convention dictates should be blue or black, represents the first discovery of the iron phosphate mineral vivianite in Asian polychrome decoration. Rare encounters with this pigment in Dutch painting of the 17th century, including in the work of Rembrandt’s first pupil, Gerrit Dou, inform this discovery and explain the contradictory color. Vivianite, known as blue ochre, is unstable. It transforms to the yellow color seen today in the Buddha’s hair by an irreversible oxidation of the iron. Recognizing this same formerly blue pigment in the painted centers of gold-petalled flowers garlanding the Buddha’s base allows us to visualize the original color scheme. It included orange-backed rock crystal flowers alternating with blue painted flowers around the base, and turquoise glass flowers alternating with orange-painted rock crystals in the mandorla.

Today, these decorations are permeated by corrosion products and mineral deposits that variously contrast with, or blend in among the original colors of the work. Survival has been selective, with discolored successors of some of the artist’s original colors, altered by the environment, alongside intact neighbors. While part of the corrosion might be removable, the majority of these transformations are irreversible. Scientific examination allows the original appearance to be appreciated for what remains and predicts that some aspects of the original appearance cannot be recovered through any form of treatment. It shows that the stripping of corrosion, once conceived as the appropriate means of revealing a gilded surface, instead would have misrepresented these two works. A successful treatment of that kind would expose them in a way that their makers never intended them to be seen and skew modern understanding of the art of the period. Such cases pose a challenge to all concerned but they also present opportunities—to collectors, in their stewardship of the art, to foster scholarship and high standards of care; to the conservator, to exercise restraint and to consider the potential for new discoveries; and to the scientist, to not merely record what remains but to interpret its origins and reconstruct the artist’s methodology.”

Details of this work may be found in the following publication:

John Twilley, Polychrome Decorations on Far Eastern Gilt Bronze Sculpture of the Eighth Century, In Scientific Research on the Sculptural Arts of Asia, Proceedings of the Third Forbes Symposium at the Freer Gallery of Art, J.A. Douglas, P. Jett, and J. Winter, eds., Freer Gallery of Art, Washington, 2007, pp.174-187

Bronze Avalokitesvara with painted details, late Sui-early Tang dynasty (8th century)

Some questions and answers about metal conservation:

1. Can the corrosion be removed to allow the original gilding to show? If not, why not?

For these two cases, we now know that the original decoration was not a uniform layer of gilding. It involved paints applied atop the gilding to contrast with it. The corrosion now permeates the paint. Removing the corrosion would result in removing the paint to give a stripped-down gold surface that was never intended to exist alone. From a practical standpoint, corrosion has undercut some of the gilding so that the gilding now adheres to the corrosion on top better than it does to the original surface below, from which it may easily be lost. As the photo detail of the face of the Avalokiteshvara showed, removing the external corrosion leads to in an uneven result with dull, copper-colored areas alongside bright gilding and remnants of the paint.

2. I collect early (Momoyama Period) steel Japanese tsuba (sword guards). Often, these objects present with varying degrees of rust. Should ALL of this rust be removed?

Rust that is orange in color is not necessarily active, though it may be. Iron rust is often exacerbated by chloride salts that cause even more trouble for iron than they do for bronze. In severe cases, droplets or weeping trails of orange liquid may develop because the iron chlorides have such high affinity for moisture in the air. This can cause the problem to migrate, damaging new areas. Because the chloride is never consumed, it goes on stimulating further corrosion. The chlorides responsible for this need to be removed as thoroughly as possible because suppressing this kind of corrosion by maintaining a sufficiently dry environment is almost impossible, even in a museum case. A good solution usually involves a combination of removal of accessible chlorides, treatment by a corrosion inhibitor, and housing in a dehumidified enclosure. The latter implies a continuing need for maintenance.

3. How is “proper condition” of conserved objects determined, exactly? Who decides?

The decision needs to be based on a dialog between the art historian/archeologist/historian, the conservator, and owner, but a dialog that is informed as fully as possible about the ramifications of treatment that may impact materials associated with the item of primary interest. For example, an understanding is taking hold in paleontology that “preparing” skeletons often results in the erasure of vast amounts of information in the form of fossil remnants of soft tissue, feathers, hair, etc. that were not formerly recognized to have survived. X-ray tomography systems are now coming on-line that are capable of discerning things as minor as an insect fossil inside a block of stone. So paleontology is looking toward a future in which physical divestment of fossils will be greatly reduced or reserved for duplicate specimens. In archaeological artifacts, we routinely see equivalent cases of the preservation of cloth, leather, pigments, lacquer coatings, and other associated goods in the form of corrosion pseudomorphs (early-stage fossils, if you will) that can expand an understanding of the artifact if they are not discarded in a quest to uncover something. If we are to avoid our irreversible actions being regretted by those who come after, as we regret the recarving of Greek and Roman sculpture in the 18th century, we need to minimize the impact of our imperfect understanding.

This post is part three of a three-part essay about our Webinar, Tales in Conservation. To read part one Click here. To read part two Click here.

Watch an excerpt from the Tales in Conservation webinar: