From September 8–16, it's September 2017 Asia Week in New York. Many of our participating dealers are open to the public, showcasing traditional and contemporary examples of the best of Asian painting, sculpture, ceramics, photography, jewelry and object design. Think of it as a teaser for the March 2018 edition of Asia Week New York! Here's our guide to the exhibitions on view. Many shows remain open past September 16—please check each listing below for details.

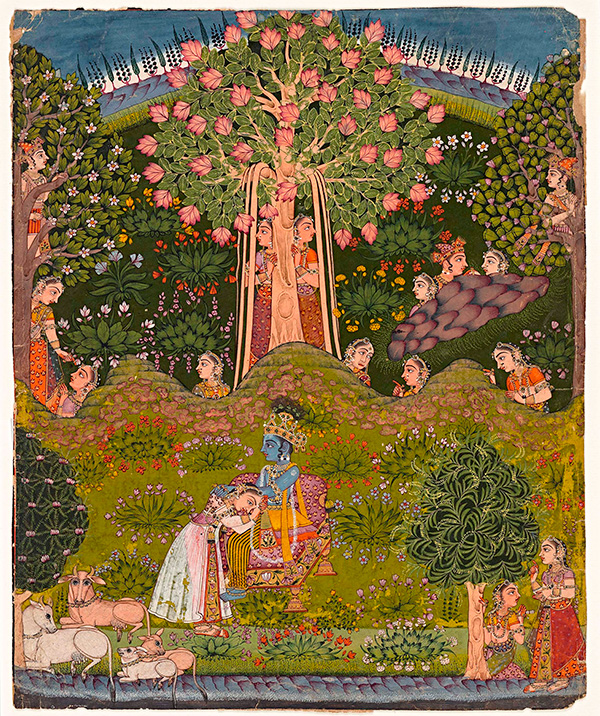

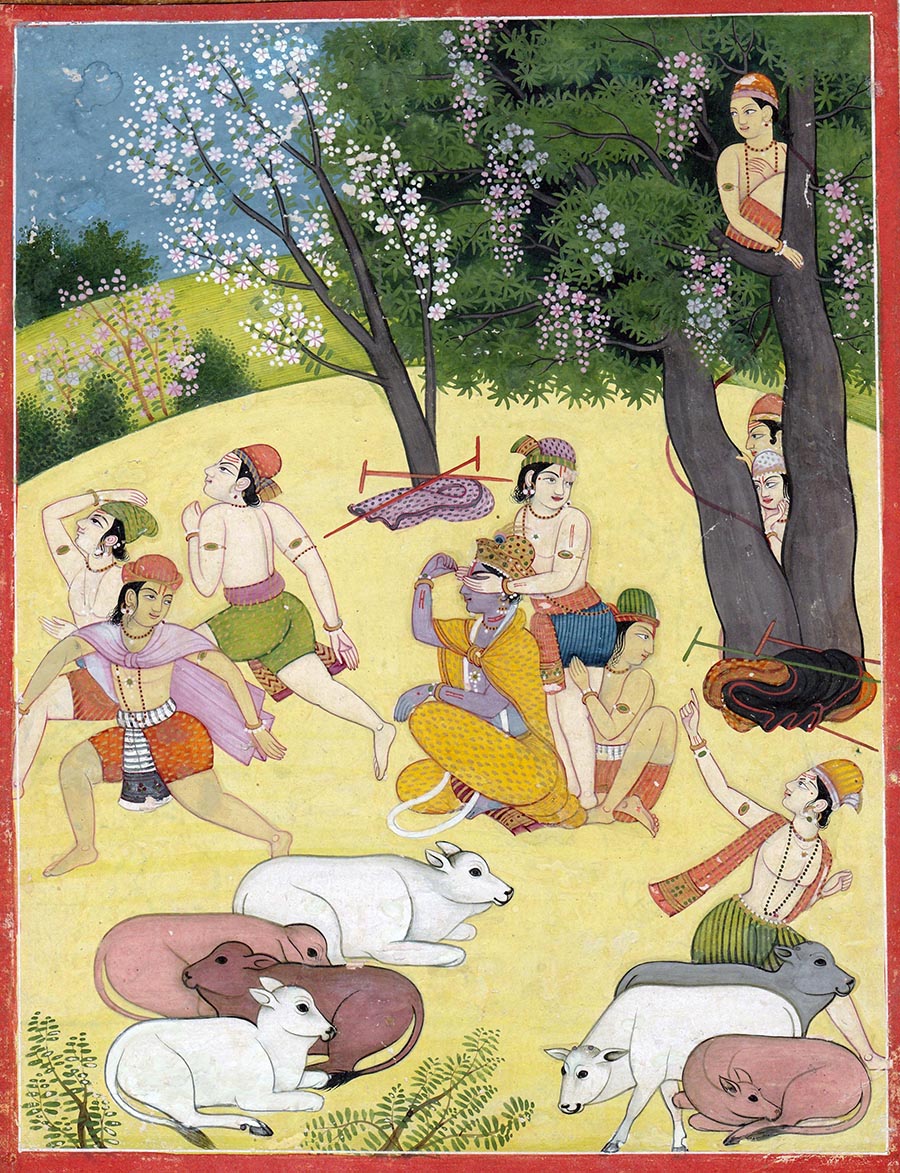

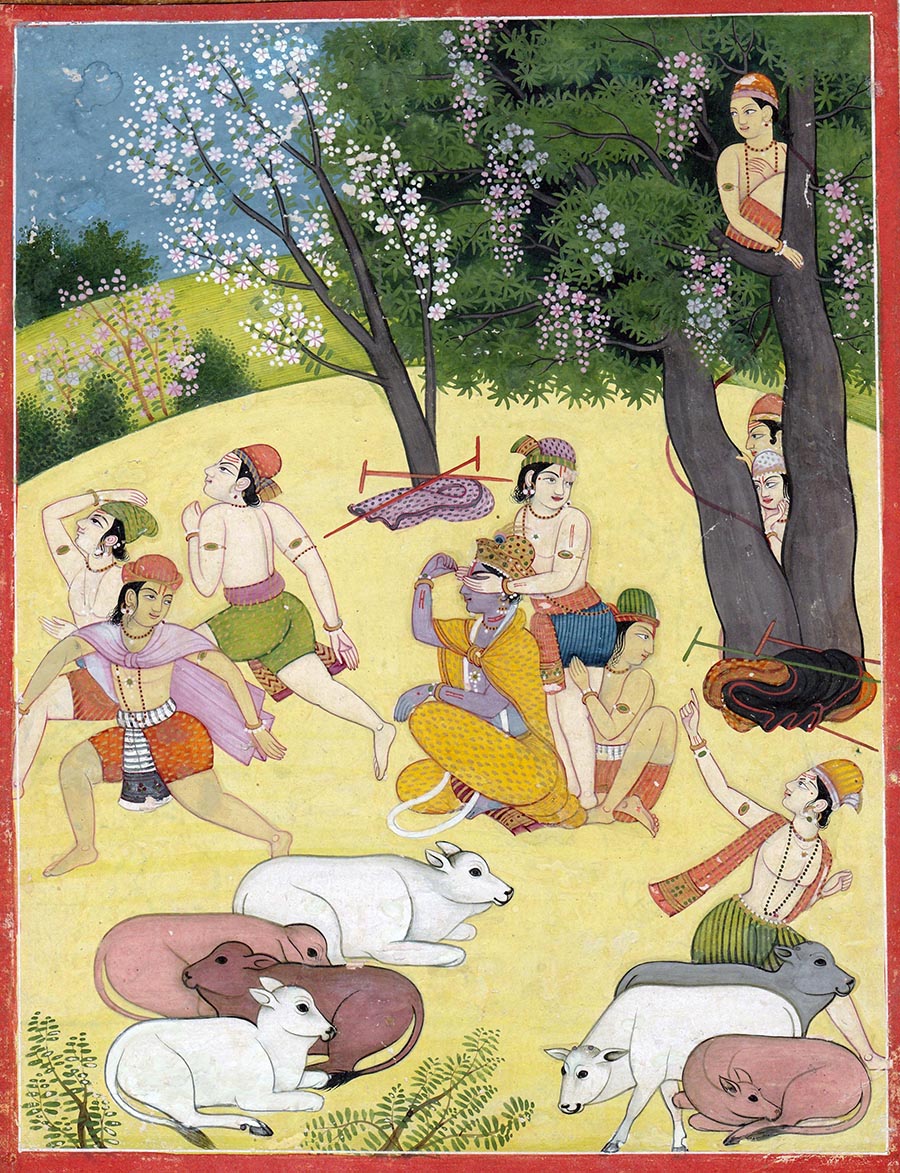

Blind Man’s Buff/Hide and Seek. Pahari, Kangra, India, circa 1775-80. First generation after Manaku. Opaque watercolors heightened with gold on paper. 10 x 8 in. (25.4 x 20.32 cm.)

Kapoor Galleries is presenting “A curated selection of works from India and the Himalayas,” including this depiction of Blind Man's Buff, a game of six or seven players. “One of them, 'the thief' has their eyes covered, while the others hide. The thief then runs in search of the others. Those who have hidden try and return to the khutavam, the place where the thief’s eyes were shielded. If the thief can touch a player before he reaches the khutavam that person becomes the next thief. The subject is a deep allegory, as 'everything is illusory: the natural world is subsidiary to Krishna’s game; and to the moral lesson it teaches.'” On view September 8–16, Monday through Friday from 10am to 5pm, at 34 East 67th Street.

A Chinese Jichimu (“chicken-wing wood”) Brushpot. Height: 18.4 cm. Qing dynasty, 19th century A.D.

A Korean Lacquered-Bamboo Brushpot. Height: 21.5 cm. Joseon dynasty, Late 19th-early 20th century A.D.

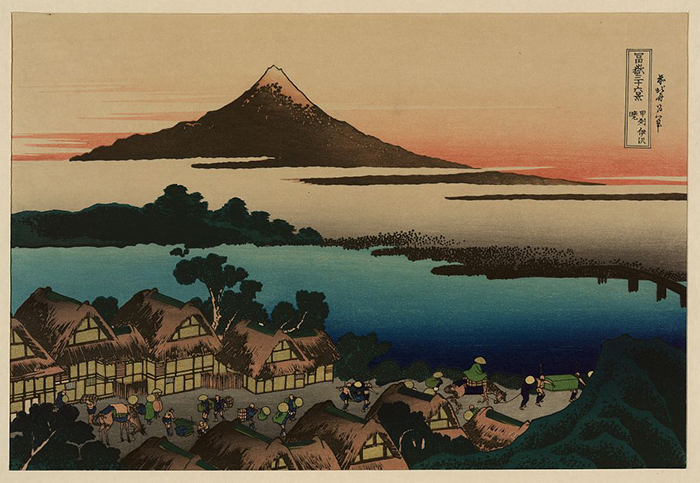

The title of Kaikodo’s fall exhibition in New York, “Sharpening the Tools: Imagery and Accoutrement from the Scholar’s World,” was inspired by a passage from the Confucian Analects: “The Master said: ‘The workman who wishes to perfect his craft must first sharpen his tools.’” This exhibition focuses on those “tools” and on images inspired by the world of the “workmen”—the calligraphers and painters, the scholars and officials of East Asia. The tools, popularly referred to today as scholars’ objects, include everything a literatus requires to do his or her work—inkstones, waterdroppers, seal-ink boxes, brushpots—to objects gathered for inspiration, such as scholar’s rocks. The exhibition also focuses on paintings depicting subjects ranging from historical gatherings of scholars to landscapes where a small hut deep and high in the mountains is the only signal of the scholar within, enjoying escape from the dusty world. The Kaikodo exhibition will feature scholar’s objects from China, Japan, Korea and Vietnam as well as paintings of the literati life from China and Japan. On view September 8 through December 9, 2017 at 74 East 79th Street in Manhattan.

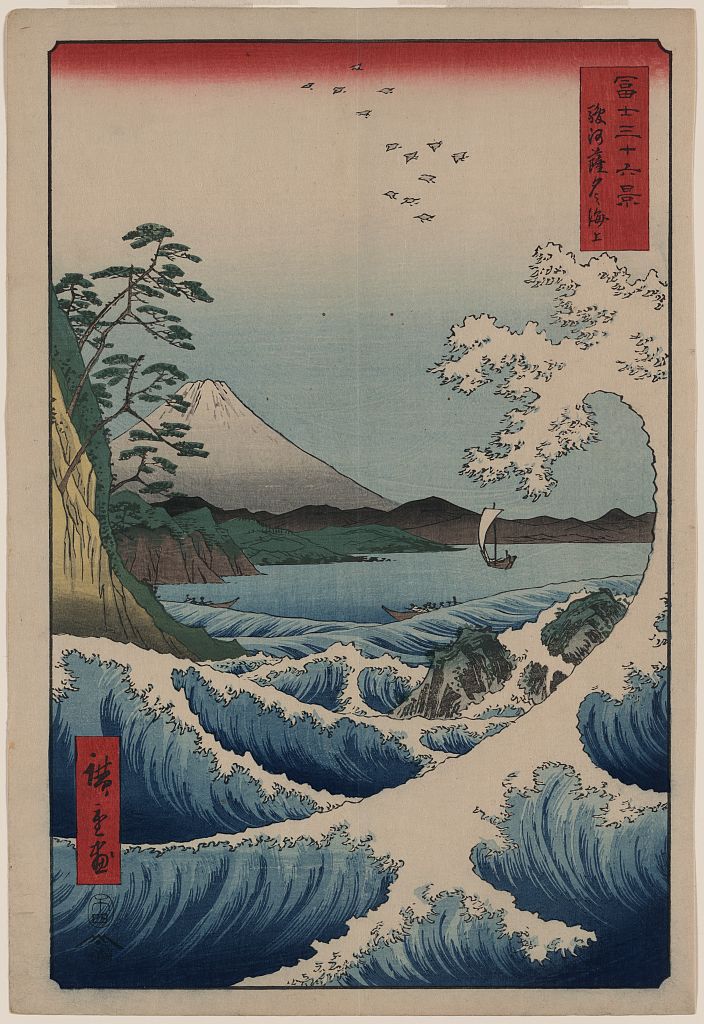

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1839-1892), Eight Views of Warriors in the Province: Fushimi in Yamashiro, 1871, woodblock print 14 1/4 by 9 1/2 in., 36.1 by 24.1 cm

Scholten Japanese Art is presenting “Darkening Skies: The Tumultuous Times of Tsukioka Yoshitoshi,” a continuation of the gallery's March 2017 landmark single-artist exhibition on Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1839–1892), one of the last great ukiyo-e artists of the 19th century. Drawing from a collection assembled over a period of nearly ten years and recently published in a full-color catalogue featuring 180 prints, the September show will display approximately 40 prints that focus on the dynamic and tumultuous times in which Yoshitoshi lived, as reflected in some of his more violent imagery. “In the end, Yoshitoshi’s oeuvre is a manifestation of the supposition that without the darkness, there can be no light,” says gallery director Katherine Martin. On view September 7–15, 2017 (Monday through Friday, 11–5) at 145 West 58th Street, suite 6D.

A gold and ruby ring. Java, 9th-12th century. Size: UK N US7. Weight: 31 grams

Sue Ollemans Oriental Art presents “Ancient Rings” from the Near to Far East, with Greek, Roman, Phoenician, Sassanian, Kushan, Indian, Khmer, Thai and Indonesian examples dating from the 5th century BC up to the 19th century. It has been suggested that the ring pictured above—of tapering circular cross section shank and with an ovoid-shaped bezel containing three cabochon rubies—represents the Hindu Trinity. The exhibition runs from September 11–16, every day from 11am–5pm, at 790 Madison Avenue, Suite 705.

From top to bottom:

HATTORI MAKIKO (b. 1984). Flow. 2016. Unglazed Porcelainous Stoneware. 13 3/8 x 15 3/8 x 15 3/8 in.

KINO SATOSHI (b. 1987). Oroshi-loop 16-47. 2015. Glazed porcelain. 12 1/2 x 25 x 3 1/8 in.

TAKEMURA YURI (b. 1980). Wan mei “Kinginka”: Teabowl “Gold Silver Flower”. 2017. Glazed porcelain, silver and gold leaf. 3 1/2 x 5 x 5 in.

Image by Richard Goodbody

Joan B Mirviss LTD presents “Rising Stars: Hattori Makiko, Kino Satoshi and Takemura Yuri,” an exhibition that showcases three young artists in their first solo exhibitions in the United States. “Hattori Makiko, Kino Satoshi, and Takemura Yuri ave each chosen a highly independent, creative approach to clay that challenges the centuries- old, established traditions of Japanese ceramic art. In the dozen works created for Inside Out: Meditative Forms of Hattori Makiko, the artist has created a captivating body of work that commands close-up viewing with her incredibly intricate, sensuous, yet surprisingly sharp surfaces. Confronting the historically significant art of celadon-glazed porcelain, Kino Satoshi tackles this esteemed tradition with his highly original approach in Quiet Tension: The Sculptural Art of Kino Satoshi. Takemura Yuri, in Dancing Colors of Takemura Yuri, takes the concept and form of the revered Japanese teabowl in a totally new and delightful direction. With contemporary sculptural forms, exquisite glazes, painstakingly intricate and challenging techniques, and refined aesthetics, these three artists have become the young leaders of the next generation of Japanese clay artists,” reads a statement from the gallery. On view September 12 through October 13 at 39 East 78th Street, Monday through Friday from 10am to 6pm.

Koshu Endo (b. 1954), Magical Clouds, 2017, UV inkjet print on UV filtering plexiglass, h. 23 5/8 x w. 35 1/2 in. (60 x 90 cm)

Onishi Gallery showcases the work of Japanese photographer Koshu Endo in an exhibition titled “O-Tsukimi,” after the annual Japanese festival centered around the viewing of the autumn moon, which happens to be celebrated during the period of this exhibition’s opening. “Timed with this ancient lunar event, this show features eight large format photographs on the theme of the moon. In addition, Endo will create a gallery installation that allows visitors to experience the ‘O-tsukimi’ rituals and learn about the history of the festival. These include ritualistic food and drink offerings, and traditional expressions of admiration for the sacred deity that is the moon,” reads the gallery statement. This is Endo's first solo exhibition in the United States. On view September 7–16 at 521 West 26th Street, Tuesday through Saturday, 11am–6pm.

An Ho (b. 1927) 安和 (生于1927). Misty Landscape of Woodstock, NY. 2017. Ink and color on silk. 7.875 x 22.75 in. (20 x 57.8 cm). Signed An Ho with one seal: An Ho

China 2000 Fine Art presents five recent paintings by An Ho who at 90 is yet discovering novelty in the beauty that surrounds her, painting her vision on silk and paper with ever-steady hands and a freshness that astounds. “An Ho’s landscapes are her own poetical fantasy, part memory, part dream,” reads the gallery statement. “Her scenes achieve nobility by their pure expression of a tranquil understanding of the universe, of the harmony between man and nature.” The artist's works have been exhibited in China, Taiwan, Germany, Italy, France and the United States, and are in the permanent collections of several museums and private collections in both the Far East and the West. “An Ho: Recent Paintings” is on view September 6–28 (Monday–Thursday from 11–5) at 177 East 87th Street.

Maha Akshobhya. Nepal, Kathamndu. Dated to Samvat 897, 1776 AD. 22.5 cm (8.85 in). Gilt Copper Alloy.

Walter Arader is presenting an exhibition of new acquisitions, featuring a dated Nepalese figure of Maha Akshobhya and a large gilt wood figure of a protectress from the Kangxi court. On view from Monday, September 11 until Monday, September 18th from 10 am until 6 pm daily at 1016 Madison Avenue.

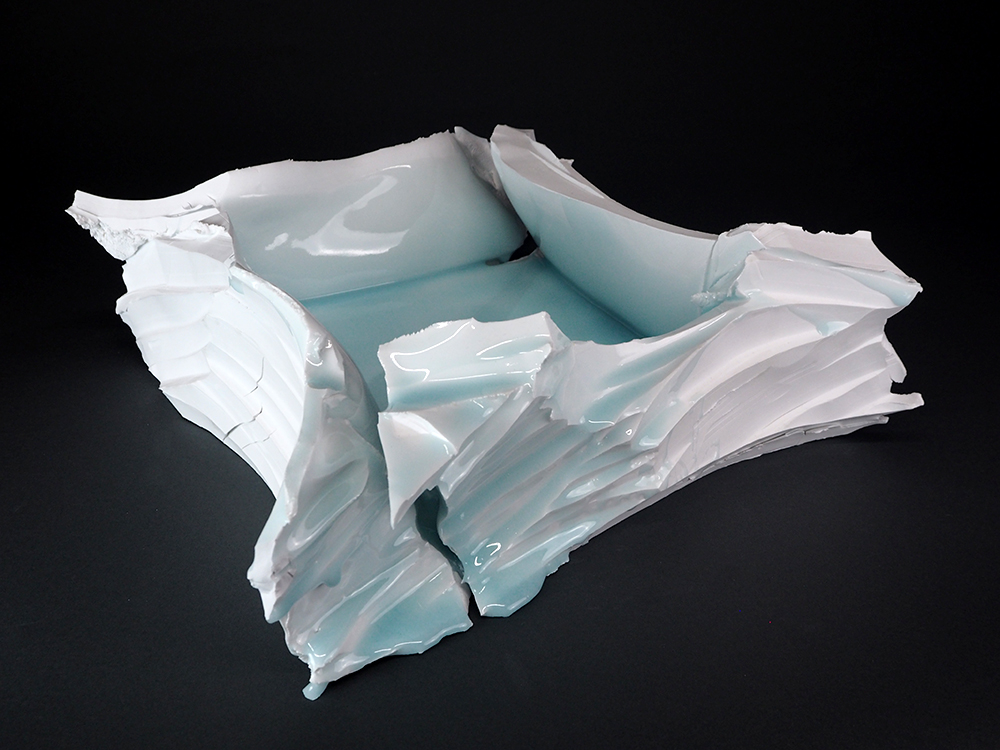

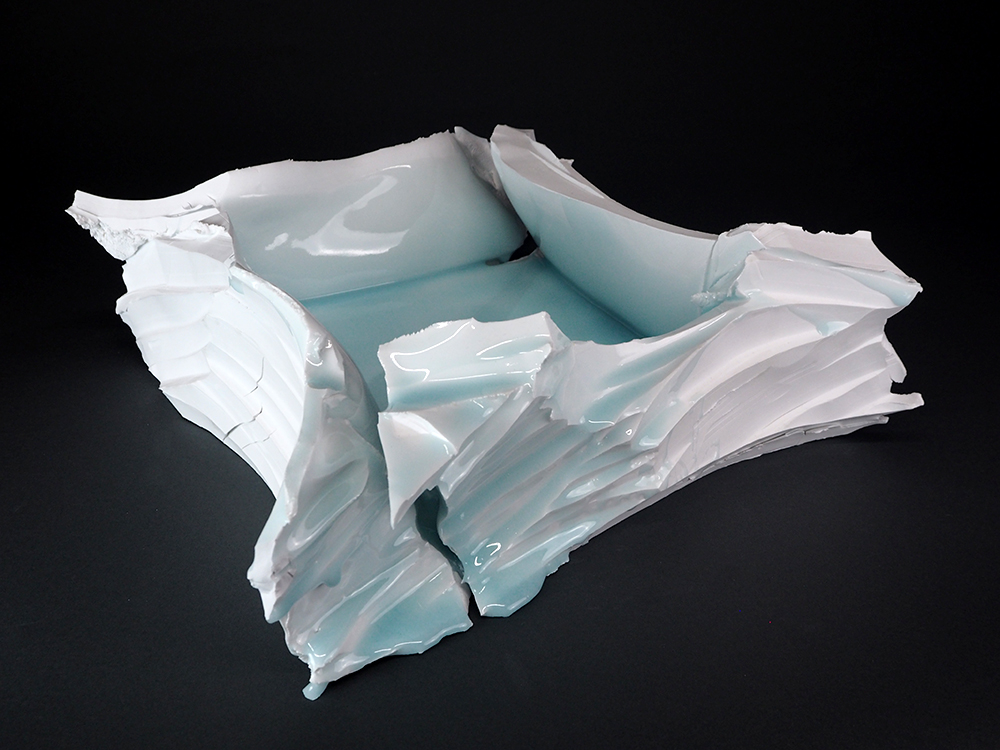

KATO Tsubusa 加藤委 (1962- ). Square Bowl. Glazed Porcelain. H6″ x D16.5″ x W17″

Dai Ichi Arts, Ltd. presents “Many Shades of Celadon,” with works by modern masters of Japanese ceramics that illustrate the medium's wide range. “Fukami Sueharu’s elegant, sky blue evocations of natural forces transcend the earthy roots of the ceramic arts. Kato Tsubusa’s tender celadon glazes shower over his unique white porcelain, which gives his work a kind of luminous glow. A more subtle crackle graces the surface of Suzuki Sansei’s egg blue celadon wares,” reads a statement from the gallery. On view September 12–22 at 18 East 64th Street, Suite 1F.

Jyoti Bhatt, Still-Life with Parrot, 1955. Oil on board, 16.2 x 28 inches.

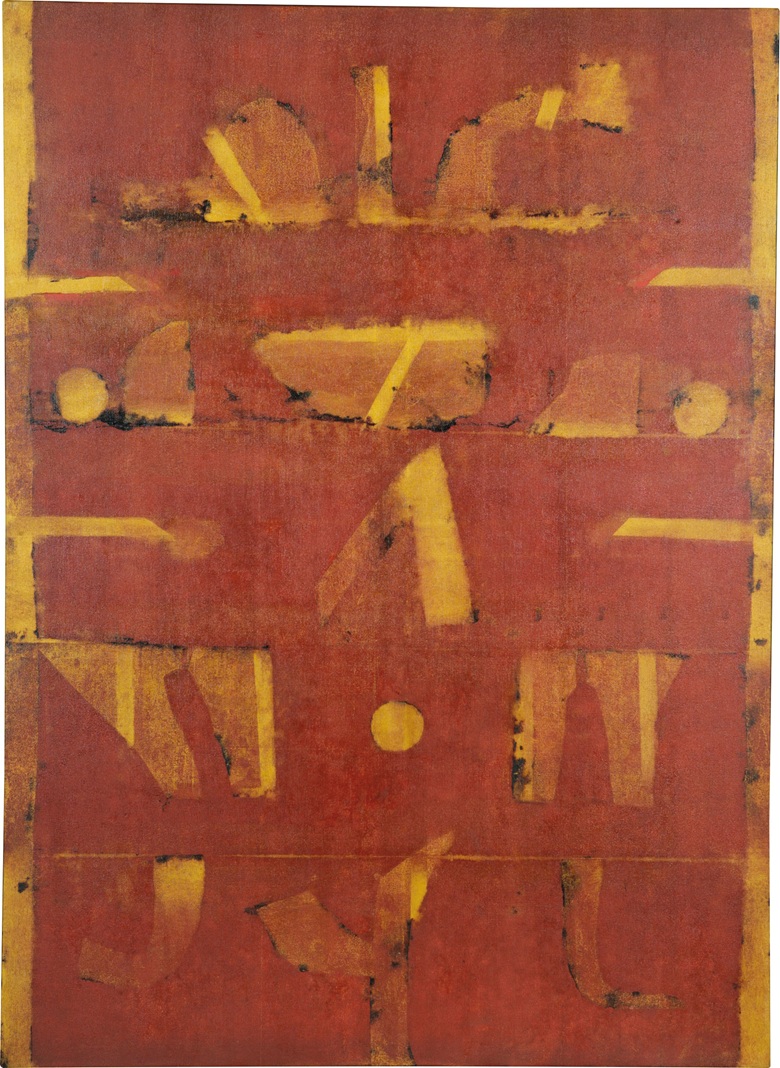

DAG Modern presents “Group 1890: India's Indigenous Modernism,” a commemorative exhibition that examines the story of Group 1890's rise and later disbanding from the perspective of the ensuing decades. It features artworks from the 1960s and later decades by the member artists – J. Swaminathan, Gulammohammed Sheikh, Himmat Shah, Jeram Patel, Ambadas, Jyoti Bhatt, Raghav Kaneria, Reddappa Naidu, Rajesh Mehra, Eric Bowen, S. G. Nikam and Balkrishna Patel. The exhibition traces the importance of these artists, through their individual art practice, and the position they advocated as a group in 1963 when they issued a group manifesto. DAG Modern’s exhibition is the first to bring the work of these twelve artists under one roof, under the rubric of Group 1890, and examine their historical significance. On view now through September 30, 2017 at 41 East 57th Street, Suite 708, Tuesday through Saturday from 10am to 6pm, and on Mondays by appointment.

Ding Ware Carved Peony Plate, Northern Song Dynasty. 22.8 cm diameter.

Zetterquist Galleries will be featuring an important Ding Ware Carved Peony Plate from the Northern Song Dynasty. This piece is remarkable for its masterful carving of intertwined stalks of peonies, the only other published example of which is from the National Palace Museum in Taipei. The piece is in excellent condition, and from a private Japanese collection. Six other Ding-yao and related Xing and Dongyanyu kiln pieces will also be on view, offering an exceptional opportunity for viewers to compare the piece above with others from the 10th through 13th centuries. On view September 9–16, by appointment, at 3 East 66th Street, #1B.

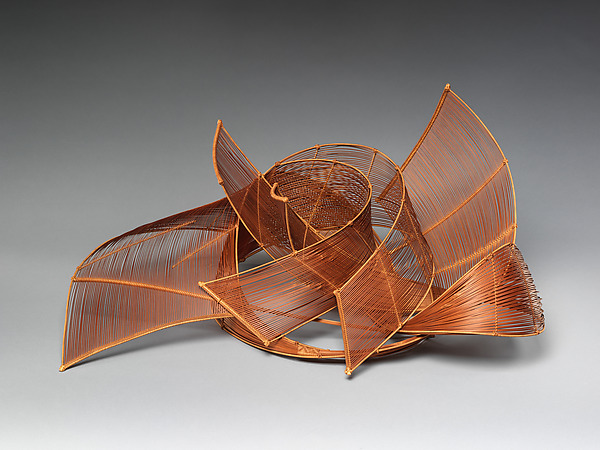

Ishikawa Shōun (1895-1973), Handled Hexagonal Flower Basket, Showa era (1926-1989), circa 1950-1980, H 14 3/4 in. (37.5 cm)

Erik Thomsen Gallery presents “Masterpieces of Japanese Bamboo Art,” highlighting works by some of the most prestigious names in the history of this medium, including Tanabe Chikuunsai I and Iizuka Rōkansai, who is represented by no fewer than nine outstanding and varied pieces. “Our selection establishes Japanese basketry as one of the great East-Asian art forms and affirms our confidence in the important role it is set to play in the international art market, with major collectors active throughout the Americas, Europe, and China, as well as in Japan itself,” says Erik Thomsen. “The timing is especially auspicious, since 2017 has already proved to be a pivotal year for the worldwide appreciation of Japanese basketry thanks to two major exhibitions: 'Bambu: Histórias do Japão' in São Paulo, Brazil, and 'Japanese Bamboo Art: The Abbey Collection' which opened at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, on June 13.” The exhibition at Erik Thomsen Gallery is on view from September 11 to November 10, Monday–Friday from 10am to 5pm, at 23 East 67th Street.

Myong Hi Kim (B. 1949). Girl. Oil pastel on chalkboard. 20 1/2 x 14 1/4 in. (52 x 36 cm)

HK Art and Antiques LLC presents an exhibition of contemporary Korean art entitled “Life Movement.” On view at September 13–23, Monday through Saturday from 11am to 5:30pm, at 49 East 78th Street, Suite 4B.

A cast and chased parcel-gilt bronze incense burner. Ming / Qing dynasty, 17th century. 5 x 5 1/4 in.

Nicholas Grindley is exhibiting some pieces from the private collection of Ken Greenstein. The selection of Chinese scholars’ objects shown reveal some of the more personal pieces belonging to the New York-based collector. He originally started out with an avid interest in snuff bottles but over the years his passion for Chinese art saw him collect a wider range of scholars' objects. He explains that this transition enabled him to discover exactly how profound and interesting scholars’ objects could be and embarked to collect a variety of pieces. On view September 11–15, daily from 10am to 5pm, at Hazlitt, 17 East 76th Street, 2nd Floor.

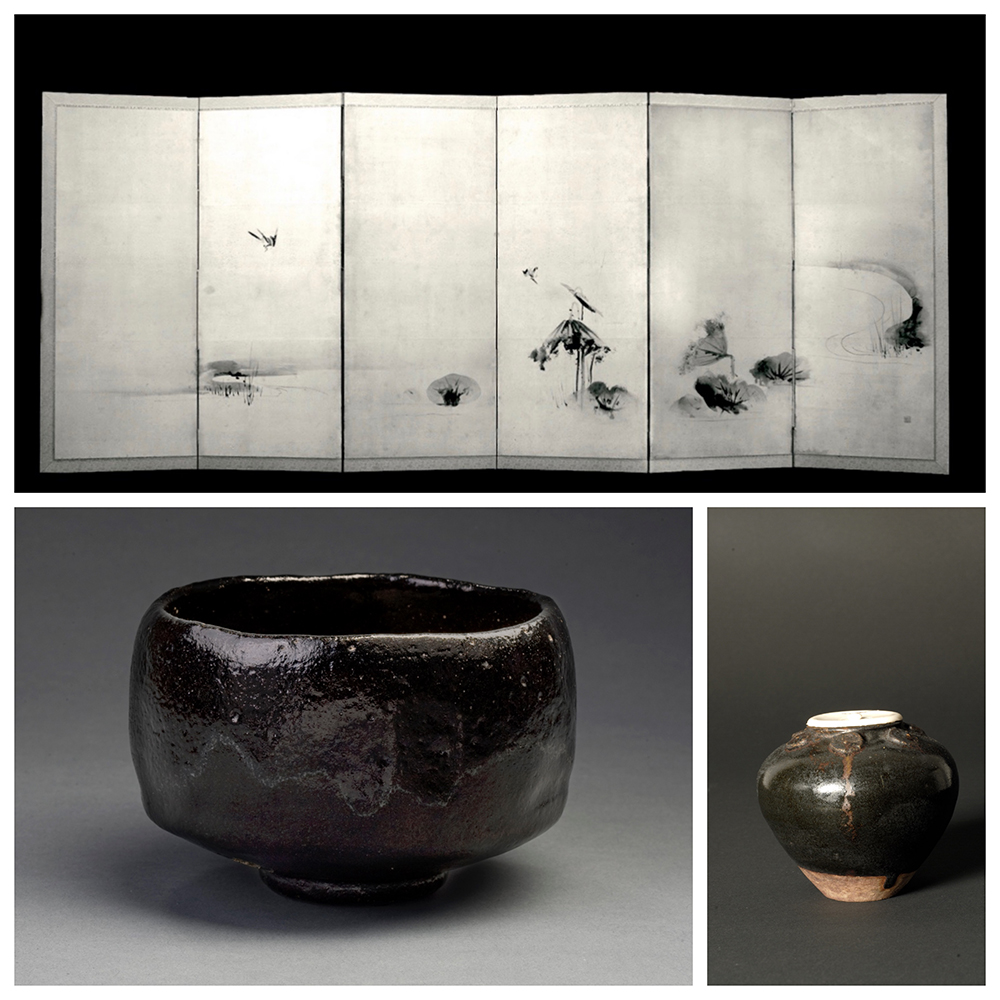

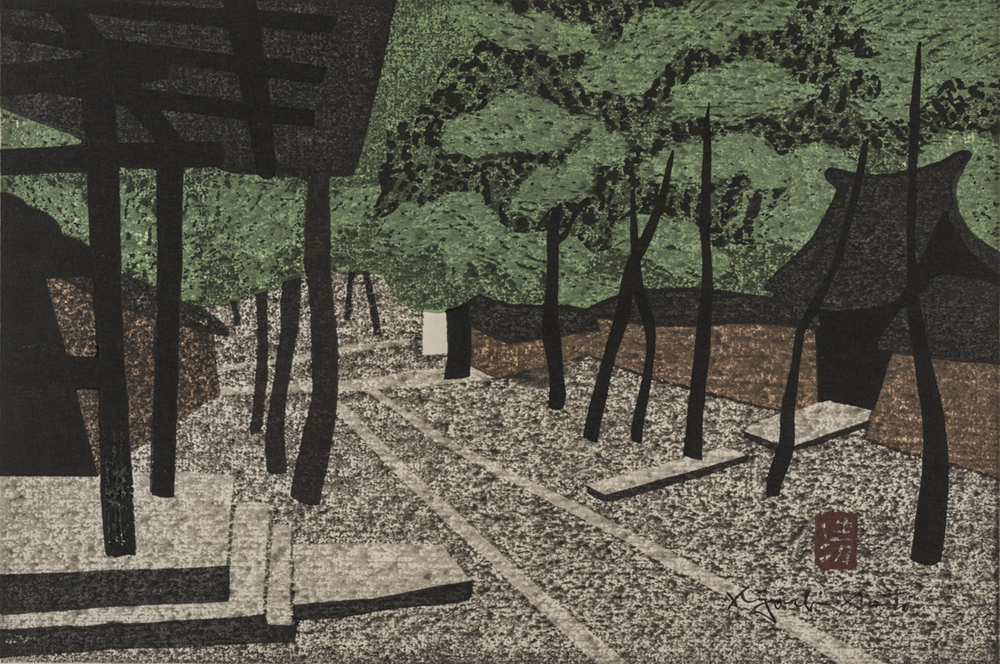

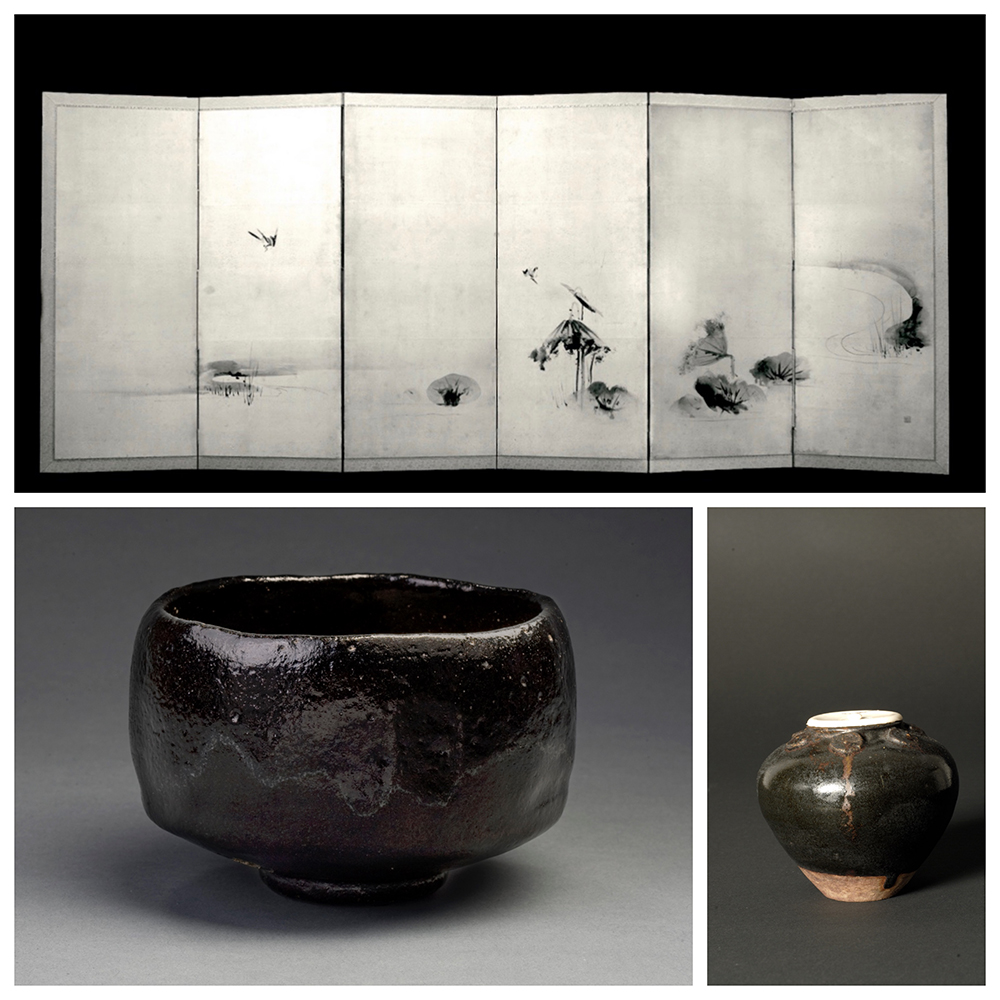

Carole Davenport presents a sneak peek of her October exhibition “ZEN INK & CLAY” along with recent acquisitions on September 11–13 from 4 to 7pm daily (or by appointment) at 131 East 83rd Street, Suite 7D. She writes: “Powerful and often unassuming ink paintings and calligraphy inspired by Zen philosophical thought expressed as calligraphic poetic phrases and spare, austere ink paintings coupled with the influence of Zen meditative outlook on tea ceremony ceramics in the form of teabowls, tea caddies and jars construct the basis of this reflective exhibition.” The complete show will be held October 26 to November 2 at Tambaran Gallery, 5 East 82nd Street, from noon to 6pm daily.