ONGOING ASIA WEEK NEW YORK EXHIBITION

Separate Realities

March 13 – June 2025

Online Exhibition

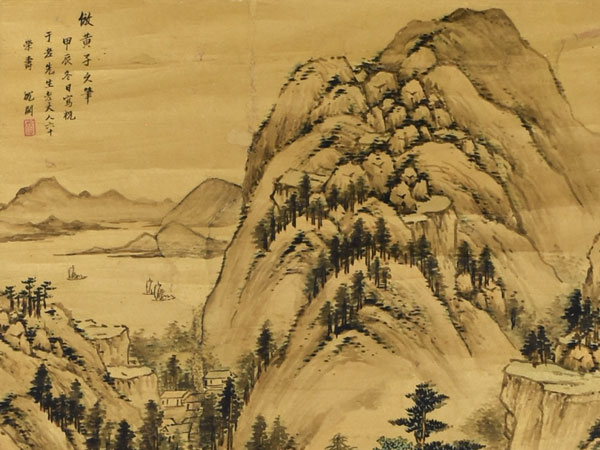

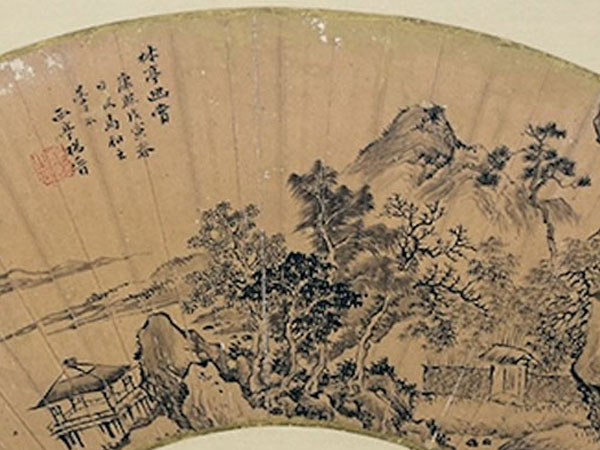

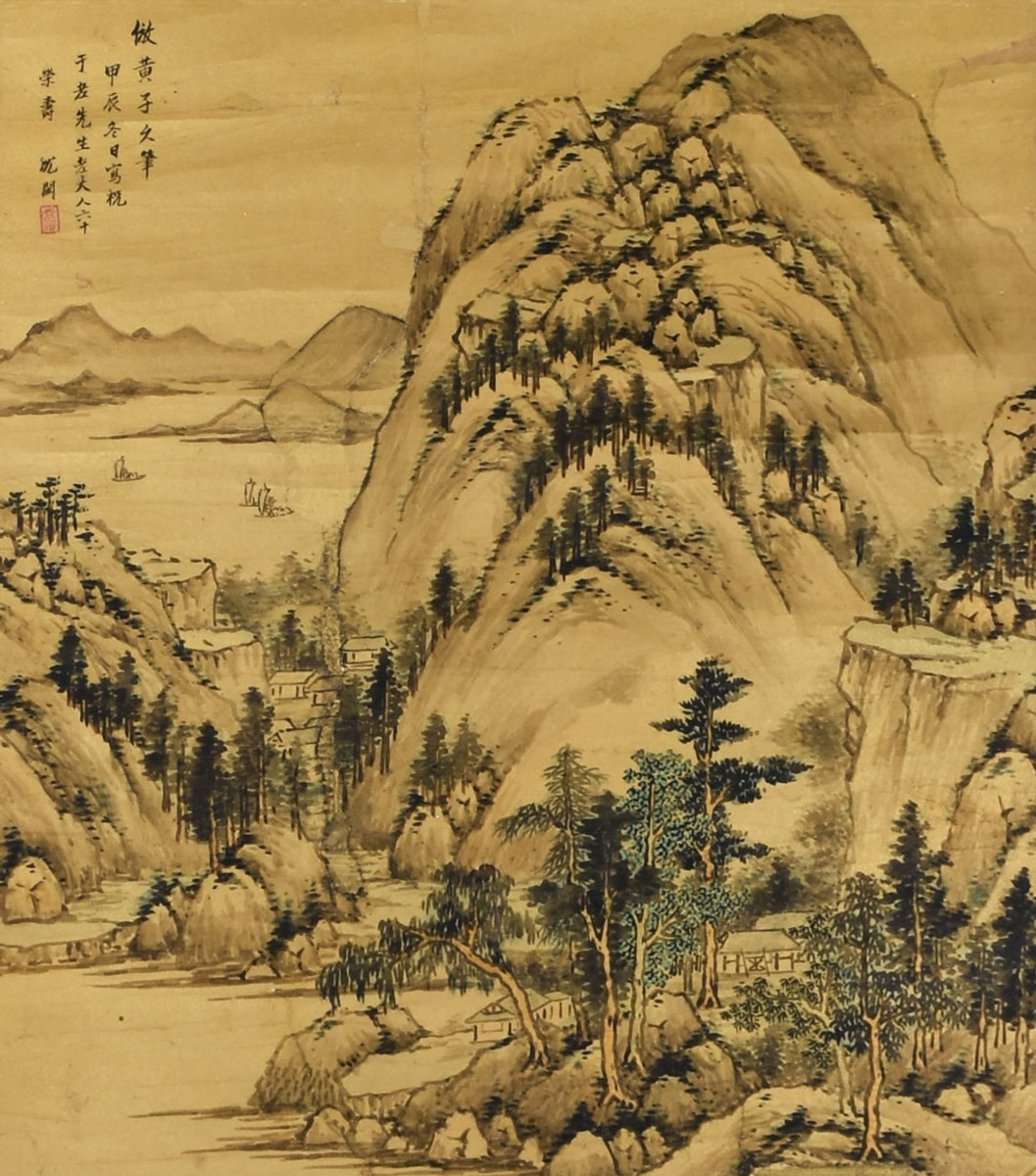

We normally approach and attempt to understand works of art by contextualizing them, by discovering comparable works that reveal them as individual members of their respective families. In the present exhibition the various works are thus presented in context but we trust that the individuality, the separate realities, of more than a few of our selected items will show through. For example, a large white stoneware vessel looks as if it must be a Tang amphora but with the neck and handles somehow loped off. However, there are no indications that it had ever had a neck or handles. It is in truth a most unusual and, in fact, quite rare vessel. Also standing out as a separate reality among a large cadre of fresh-water jars for Japanese tea-ceremony use is a Ming-dynasty bucket-shaped celadon, likely with a long history in Japan. Although the design executed in vivid enamel colors on a Zhangzhou “Swatow” ware charger is not unusual, the high quality of the painted decoration is exceptional. And completely mesmerizing is a painting of autumn grasses in moonlight by Suzuki Kiitsu (1796-1858), an Edo-period master known for his most compelling use of color. Yet here ink alone conjures autumnal colors.

Further, while gathering works of art for this exhibition, we scoured our inventory searching for reptiles that might be lurking there, motivated by a desire to celebrate the Year of the Snake. We were not disappointed. Fitting the bill was a knot of vipers on an Eastern Zhou bronze appendage and many writhing on the surfaces of a pair of bronze axle caps of the same period. Added to these is an elegant Song-period yingqing ceramic official coddling in his hands a small, coiled snake along with an earthenware rendering of the sixth sign of the Chinese zodiac from a set of twelve from the Yuan dynasty, and finally a menacing snake careening toward a group of terrified villagers in a section of a 19th century Japanese handscroll. Snakes were presented in these works in strikingly different ways, from place to place, from medium to medium, from period to period. Different worlds; separate realities.

We are illustrating here a few examples among the Chinese and Japanese paintings and objects in our online exhibition and invite you to visit our online catalog here to view the entire show, fully illustrated and with our usual writeups.

Kaikodo Hawai’i

We established Kaikodo in Japan in 1983 as a Japanese company, encouraged by friends and associates there who would become for a long time our most valued clients. During our years in Japan, we lived in and worked out of a hilltop house on grounds owned by a sub-temple of Engaku-ji in Kita-Kamakura. It was a magical place, a magical time. At some point, however, we thought we might add some bright city lights to our lives. In 1994 we found an irresistible building on the Upper East Side in New York City, renovated it, opened Kaikodo in its new locale in 1996, and because of the amazing staff we worked with, we were able to retreat to some very remote digs on the Big Island of Hawaii, which would serve as our primary residence and the center of our research, writing, and buying forays to Asia, a stone’s throw away. It was natural when the pandemic hit and made business in NYC impossible for us, that we move all Kaikodo operations to our home on the Big Island. Despite the mid-Pacific location and its particular challenges, our work and business continue, all made possible by our website and online exhibitions that maintain the Kaikodo Journal format, and very importantly facilitated by the good offices of Fedex and DHL.

Kaikodo Journal and Seasonal & Special Exhibitions

Entering the commercial world of Asian art as teachers and academics, it was natural that a scholarly journal would best serve us as a sales/exhibition catalogue for our newly established Kaikodo. From the beginning, we not only introduced the paintings and objects through thoroughly researched and illustrated entries, but the journal was also a venue for students and professors, curators, critics and collectors for publishing their current work.

We produced Kaikodo Journal in printed format from 1996 to 2015 and from then on issued it exclusively online. The first link below will take you to a list of journals. If you highlight a journal number, its preface will appear explaining its contents. We have also done numerous seasonal and special exhibitions in the gallery and abroad. The printed and online catalogues accompanying these shows are not numbered as journals, but they can be found in a complete listing of our exhibitions by going to the second link: Archives

A good number of our older journals and special exhibition catalogues are online. If you are interested, let us know and we can direct you to what you are looking for.

To view the Journals, click here.

To view the Archives, click here.