Francesca Galloway

Asavari Ragini

Folio from a Ragamala series

Kota, India

c. 1720

Opaque pigments with gold on paper

Folio 35.7 × 25.7 cm; painting 20.2 × 11.2 cm

Inscribed above in Devanagari in the yellow panel: 36 Shri Raga ki ragini; Asavari Ragini (in the upper right);

gav do pahro (to be sung in the afternoon)

Provenance

Collection of Eva and Konrad Seitz

Asavari Ragini, a melody to be sung in the afternoon, is almost invariably represented by a tribal woman wearing a peacock-feather lower garment as she consorts with the many serpents in the den that has swarmed the grove, albeit in a surprisingly unmenacing way. In most regional expressions of the Rajasthani tradition, a dark-skinned woman sits alone on a boulder or hillock, playing a flute to tame the creatures. In this case, however, the artist has invigorated this standard imagery in several ways: refining the woman’s complexion to a light shade of blue and her bodice to a sheer golden article, wreathing her rocky throne with both a dramatic strip of grass and a lotus-filled stream teeming with fish and fowl, and transforming her musical instrument into a small elephant goad, which she plies benignly above the serpent’s head as a patient instructor might. A longer jewelled spear or sceptre with a fleur-de-lis head lies by her feet. This same minor variation occurs in the corresponding illustration in the c. 1650–60 ‘Berlin Ragamala’.1

As is the case with several other ragamala series of the Bundi/Kota style, this series has elicited divergent scholarly opinions, with some arguing for a Bundi provenance and a date at the end of the 17th century, and others placing it in Kota at a date as late as 1720.2Joachim Bautze meticulously lists other folios from the same series, which is distinguished by its flat black ruling and presence of long inscriptions in the upper border.3 The woman here does have a sharper nose than many others depicted in this series as well as the heavy eyelids characteristic of Kota painting. The colouring is rich, even flamboyant in some passages, especially in the crimson-pink gradations in the inventively faceted rocky throne and outcrop above and the orange-streaked sunrise sky. Luxuriant foliage patterns are animated in wonderfully irregular ways, and the white froth along the shoreline is as dense and palpable as any in Indian painting. Many creatures, from ducks to scorpions to serpents, possess a delightful whimsical quality.

1. Berlin ISL I 5697, published in Ernst and Eleanor Rose Waldschmidt, Miniatures of Musical Inspiration in the Collection of the Berlin Museum of Indian Art (Berlin, 1975), fig. 110.

2. Joachim Bautze, Lotosmond und Löwenritt, cat.nos.31–32; and Bautze and Amy Poster in Amy G. Poster et al., Realms of Heroism: Indian Paintings at the Brooklyn Museum (New York, 1994), cat. no.124, take the former position; Milo C. Beach, in John Seyller, ed., Rajasthani Paintings in the Jagdish and Kamla Mittal Museum of Indian Art, cat.nos.46–47, subscribes to the latter. Losty, Rajput Paintings from the Ludwig Habighorst Collection, p. 30, accommodates both positions, maintaining that artists from both Bundi and Kota worked on the series at different dates.

3. Bautze, Lotosmond und Löwenritt, p. 95, n.10. Another folio (Nata Ragini, painting no.20) was subsequently offered at Bonhams 18 September 2013, lot 141.

Contact Gallery

Gallery Website

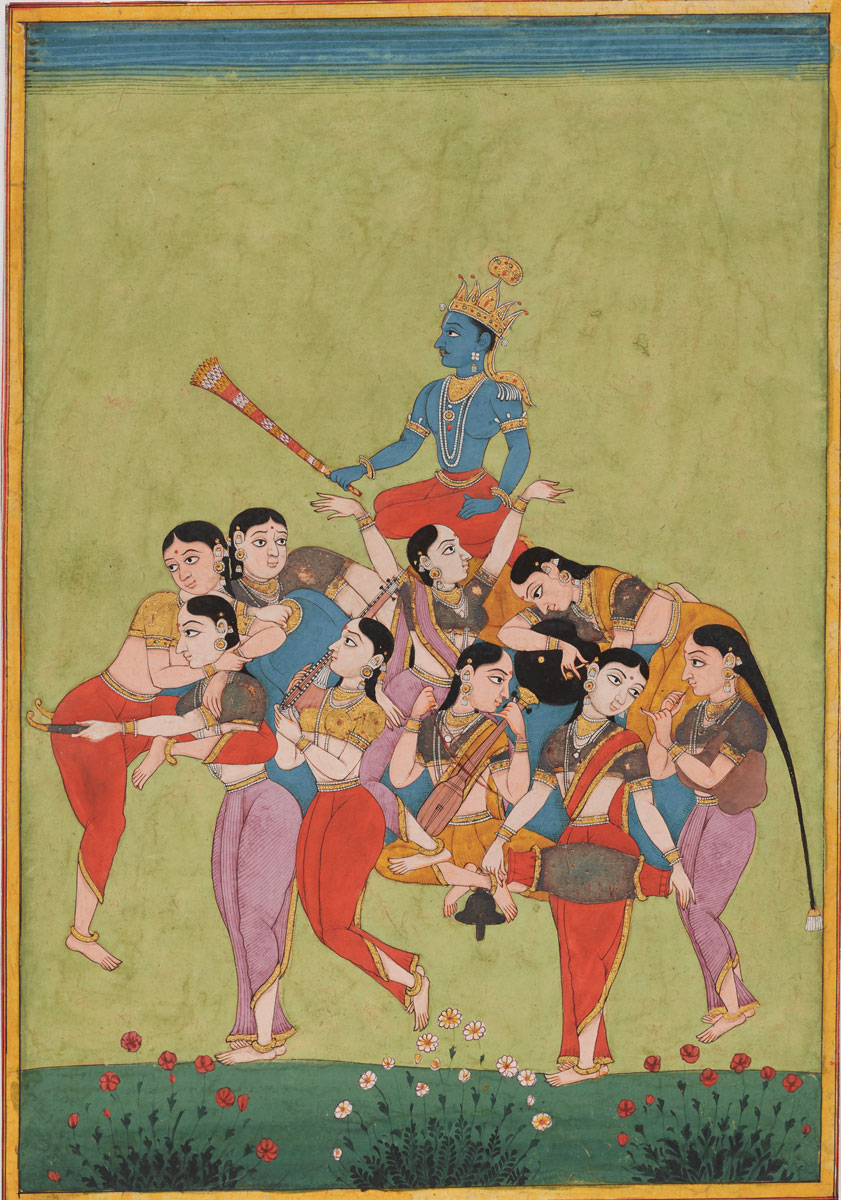

Francesca Galloway

Krishna on a Composite Elephant

Golconda style in the Northern Deccan, perhaps Aurangabad

c. 1750

Opaque pigments with silver and gold on paper

Folio 23.5 × 16.5 cm

Provenance

Collection of Zarrina and Antony Kurtz

Collection of Françoise and Claude Bourrelier, Paris, 1977–2014 Sotheby’s, 20 July 1977, lot 42

Published

Losty, J.P., Indian Painting 1590–1880, Oliver Forge & Brendan Lynch, New York exhibition, 2015

Krishna attired as a prince is riding an elephant composed of nine young women. Some are in dance poses and others play musical instruments including a tambura, sarangi, double-ended drum and unusually a bagpipe. Krishna here is a powerfully built young prince, rather than the boy who played with the gopis’ affections in the woods of Brindaban. He is wearing a gold crown with a peacock-tail finial with a dependent tail piece that covers the back of his neck and his shoulder. This latter feature is found in two representations of Krishna in a small set of northern Deccani Rasikapriya paintings in the British Library, tentatively dated 1720–30 (Add.21475, ff. 4 and 8, see Losty,)1 where Krishna wears a tall conical crown typical of southern India, see also Falk and Archer 1981, no. 427(iv)2 . The crown in our painting with its peacock finial suggests influence from Rajput court styles, indicating perhaps a provenance in Aurangabad where Rajput nobles were still serving in the Mughal armies in the Deccan.

The women wear a bodice and either a dhoti or a sari pulled between their legs in the north Deccan fashion and up over their shoulders. The ground is simply a strip of dark green-blue with sprays of flowers in front of it. The bold outlining of faces, eyes and heads slightly too large for their bodies suggest a date early in the eighteenth century (cf. Zebrowski 1983, figs. 217, 221).3 The liberal use of gold and silver leaf suggests influence from the southern Hindu icon-painting schools such as Tanjore.

The Golonda/Hyderabad style spread throughout the Deccan and southern India into Hindu court styles in ways which are, as yet little explored. Hindu paintings in early versions of styles such as ours are keys to eventually determine the process of transmission.

Whatever their original meaning, by this time such composite images had become vehicles for artists roughout India to exhibit their skill. Another example of a composite elephant from the Deccan is an early Bijapuri painting, c. 1600, of a prince riding an elephant composed of animals and figures in the Chester Beatty Library (Leach 1995, no. 9.670).4 A composite horse from Golconda filled with demons and animals is in Berlin (Zebrowski 1983, fig. 135).5 For a study of the genre with further examples and references, see del Bonta 1999, pp. 69–82.6

J.P. Losty

1. Losty, J.P., ‘An Album of Maratha and Deccani Paintings – Add. 21475, part 2’, see http:// britishlibrary.typepad.co.uk/asian-and-african/2014/06/an-album-of-maratha-and- deccanipaintings-add21475-part-2.html

2. Falk, T., & Archer, M., Indian Miniatures in the India Office Library, London, 1981

3. Zebrowski, M., Deccani Painting, London, Berkeley, Los Angeles & New Delhi, 1983

4. Leach, L.Y., Mughal and Other Indian Paintings in the Chester Beatty Library, London, 1995

5. Zebrowski, M., Deccani Painting, London, Berkeley, Los Angeles & New Delhi, 1983

6. Del Bonta, R., ‘Reinventing Nature: Mughal Composite Animal Paintings’ in ed. S.P. Verma, Flora and Fauna in Mughal Art, Mumbai, 1999

Contact Gallery

Gallery Website

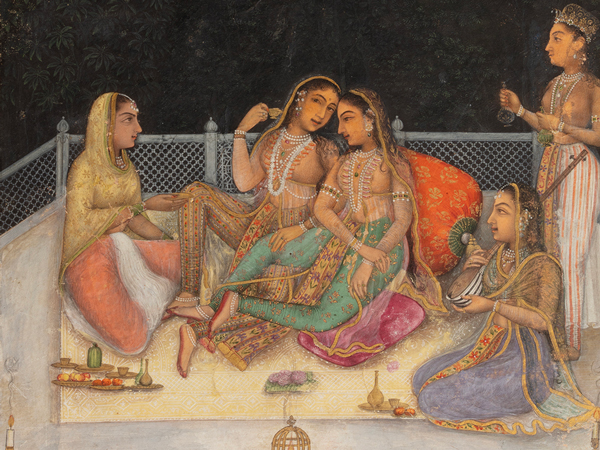

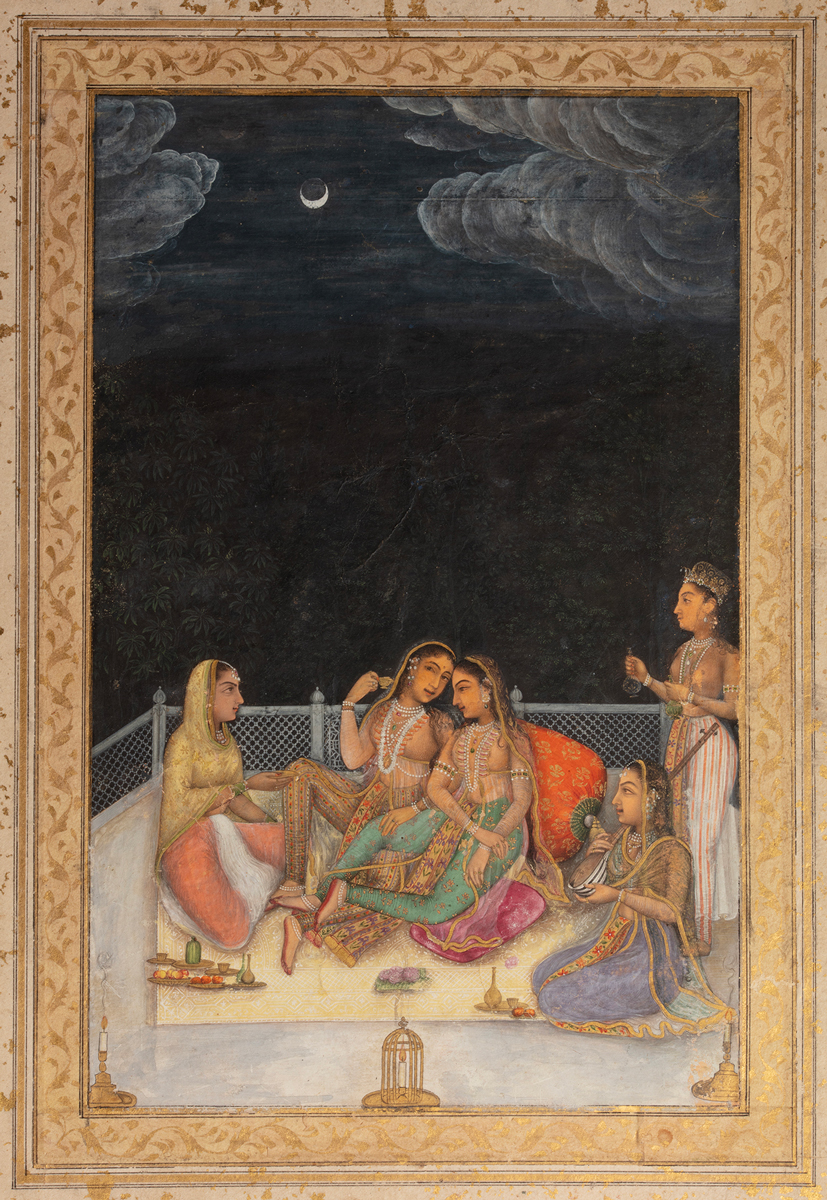

Francesca Galloway

Two Princesses Entertained at Night on a Terrace

Attributed to Muhammad Gawhar

Mughal, India

c. 1690

Opaque pigments with gold on paper

Folio 39.8 × 28.1 cm; painting 20 × 12.9 cm

Reverse: Calligraphy signed by Abu’l al-Baqa al-Musawi, dated A.H. 1098/1686–87 c.e.

22.3 × 11 cm

Provenance

Private collection, UK

Images of beautiful women relaxing in the imperial zenana must have held vicarious appeal for the Mughal court, for most men were barred by protocol from ever venturing into that highly restricted part of the palace. It is also likely that royal women themselves appreciated depictions of their own realm; in fact, one late 17th-century drawing of a gawky pre-adolescent male servant is inscribed with a note indicating that it was made expressly for the amusement of the ladies of the zenana. In such a luxurious environment, where wine and music flowed freely, pleasures were savoured, and feelings of intimacy were readily kindled.

This painting captures one such stolen moment in the zenana. On a summer’s night when the crescent moon has yet to be swallowed up by approaching cloud banks, two princesses lounge together on a terrace that overlooks a shadowy grove of loquat trees. Two attendants stand and kneel nearby, proffering the contents of delicate glass bottles and a shallow golden dish. A lone musician, her lips parted slightly in song, plucks the tambura as she serenades the pair of royal ladies. Additional vessels, fruits, and blossoms are arrayed across a yellow floor covering with an unobtrusive pattern. Most of these elements are standard in such formulaic terrace scenes.1 What creates this painting’s compelling emotional warmth, however, are nuances of glance, pose, and painting technique. The two princesses, for example, lean their heads together conspiratorially so that one princess can discreetly receive the confidential whisper of the other, who simultaneously glances outward towards the viewer to watch for potential eavesdroppers. The two women sit very close, the one extending her sprawling leg between those of her companion and the other reciprocating with a hand resting suggestively on it. Curling wisps of smoke rise from three candles, which, along with the fleeting moonlight, bathe the royal coterie in soft, atmospheric light without casting overt shadows. Most of all, every bit of warm-toned flesh is given a sensuous, palpably textured surface. For example, along with the hands and torso of the standing maidservant, the faces of the two princesses and the musician are modelled with tiny, granular marks – an effect reminiscent of the style of the Mughal master Govardhan (active 1596 – c. 1645) and unlike the taut, eggshell-like treatment of faces commonly seen in the work of such mid 18th-century painters as Muhammad Afzal (active c. 1730–40). This artist renders gold-hemmed diaphanous cloth with admirable skill, as exemplified by the sheer garments worn by the princesses, and complements it with a strikingly painterly treatment of heavier but seemingly fluffy fabrics such as those of the seated servant’s mustard-coloured shawl, peach-coloured lower garment, and white patka. One more unorthodox detail is also distinctive enough to merit mention: the scratchy striations on the figures’ forearms that describe the dense network of folds in the sheer material.

Our knowledge of individual Mughal artists operating at the end of the 17 century has deepened considerably in recent years. One painter who has not yet figured significantly in that revised account is Muhammad Gawhar (or Guhar), previously known from only two ascribed works.2 On the basis of their pronounced similarities with the present work in the exact shapes of the facial features and hands, and especially the all-over texture marks applied to the face, neck, and hands, this painting and a fine bust-length image of an elegant Mughal lady holding a cup and saucer appear to relate to Muhammad Gawhar.3 It is probable that an artist this accomplished worked for a Mughal prince such as A‘zam Shah (1653–1707), who, along with his sibling, son, and nephew, Princes Mu‘azzam (1643–1712), Bidar Bakht (1670–1707), and ‘Azim al-Shan (1664–1712), was the face of imperial Mughal patronage of painting in the decades around 1700.

Mounted on the reverse of the folio are verses from a ghazal is a quatrain of Sa’ib Tabrizi (d. c. 1676) written in nasta‘liq by the 17th-century calligrapher Abu’l-Baqa al-Musawi in A.H. 1098/1686–87 C.E. From a family of Sayyids from Abarku in central Iran, he lived primarily in Isfahan, but at one point travelled to India, where he left behind a specimen written in Shahjahanabad (Delhi).4 He was in the service of the physician Taqarrub Khan, who also emigrated to India, where he served as royal physician, as well as Taqarrub Khan’s son Mirza Muhammad ‘Ali Khan.

1. Indeed, a contemporary painting with practically the same composition and series of poses, albeit with minor differences in the patterns of clothing and floor covering and especially a bright sky at sunset rather than one representing the dark of night was offered at Sotheby’s, London, 24 April 2013, lot 82.

2. Standing Youth, dated A.H. 1103/1691–92 C.E., published in B.N. Goswamy, Jeremiah P. Losty, and John Seyller, A Secret Garden: Indian Paintings from the Porret Collection (Zurich: Museum Rietberg, 2014), cat.9; and Mirza Shaykh ‘Abd al-Rahman, ascribed on the painting raqamahu Muhammad Gawhar, c. 1690-1700, and published in Sotheby’s, London, 26 October 2022, lot 69.

3. Royal Library, Windsor, RCIN 1005068.aa, f. 25r.

4. Christie’s, 10 October 2006, lot 118. His career is discussed in Mehdi Bayani, Ahval va athar-e

khushnevisan, vol. 1, Tehran, A.H. 1345 H.sh./1966 C.E., pp. 22–24

Contact Gallery

Gallery Website

Francesca Galloway

Group of hookah bases, lidded bowl, and brass stem cup from Indian Decorative Arts and Paintings from Private Collections online catalog

Contact Gallery

Gallery Website

ASIA WEEK NEW YORK 2024

Indian Painting: Intimacy and Formality

March 14 – 21, 2024

Asia Week Hours: Mar 14-21, 10am-6pm (otherwise by appointment)

Opening Reception: Thursday, March 14 until 8pm

For Asia Week New York this March, we are pleased to present a small and exciting group of 17th and 18th century Mughal paintings, works from famous Bundi & Kota Ragamalas, a grand early 19th century Maratha processional scene by a Hyderabad trained artist, drawings for the famous Tehri Garhwal Gita Govinda series and Company School paintings including portraits of Indian children, a Skinner trooper and architectural studies of Mughal monuments and Hindu temples. Most of the paintings are recent acquisitions from private collections.

The title of this exhibition, two years in the making, reflects some of the key themes that are expressed in this group of Indian paintings. Our exhibition allows viewers to peer into this world, both intimate and formal. Amongst some of these most intimate scenes is that of a Mughal emperor, not in courtly splendour but tenderly cradling his favorite grandson, a religious gathering of devoted followers and a zenana scene more intimate than formal. By contrast, the formal scenes so often evoked in our imaginings of India can be seen in the grand processions, extraordinary tiger hunts and in formal portraits commissioned by the Emperor Shah Jahan, these paintings show us the courtly world in its stately splendor.

To learn more and view our newest catalog, click here.