NEW SUMMER WORKS OF ART

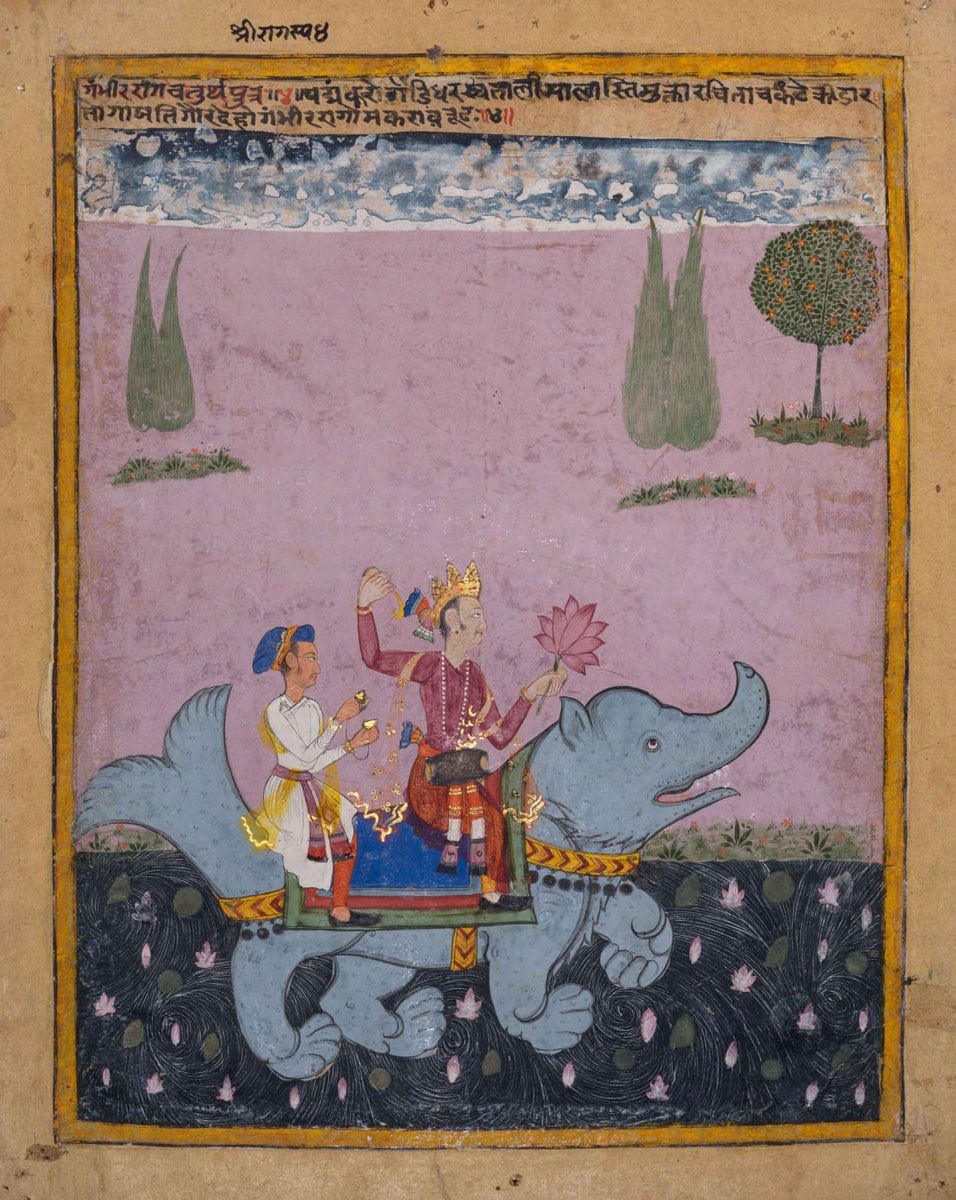

Sound, Text, and Image: Picturing Music through Ragamala

Summer 2025

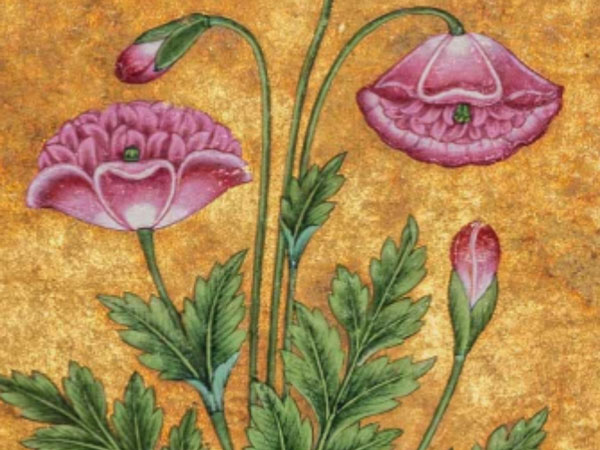

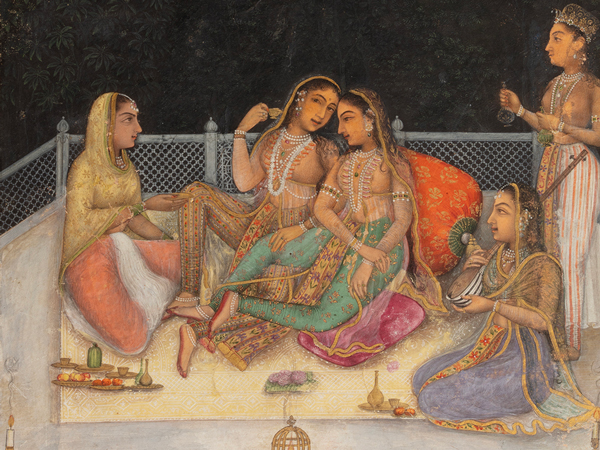

What does sound look like? In pre-colonial north India, music scholars, poets, and painters developed images and descriptions for the musical entities known as ragas, and strung them together in a series or “garland” (mala). While it is not clear precisely when listeners began to conceive of music this way, by the 1500s, ragamala poetry and paintings were well established, and proved to be extremely popular until the nineteenth century.

In his insightful essay, Richard David Williams explores how Ragamala paintings weave together sound, text, and image to create an immersive multi sensory experience—where melodies are not only heard but also seen and read. Drawing from a group of rare Ragamala paintings from the north Deccan, dating from 1630–50, Williams reveals how artists from this period used color, composition, and accompanying verse to evoke the emotional and aesthetic essence of musical modes.

His essay provides fresh insight into the cultural and historical context of these works, highlighting the distinctiveness of Deccani aesthetics, marked by lyrical compositions, jewel-toned palettes, and Persianate influences. By examining how painters translated sonic and poetic structures into visual form, Williams invites us to rethink the boundaries between art forms and appreciate Ragamala not simply as illustration, but as a unique form of musical translation. These paintings make melody visible, readable, and deeply felt.

You can read the full essay and view new works of art on our site by clicking here.

PAST ASIA WEEK NEW YORK EXHIBITION

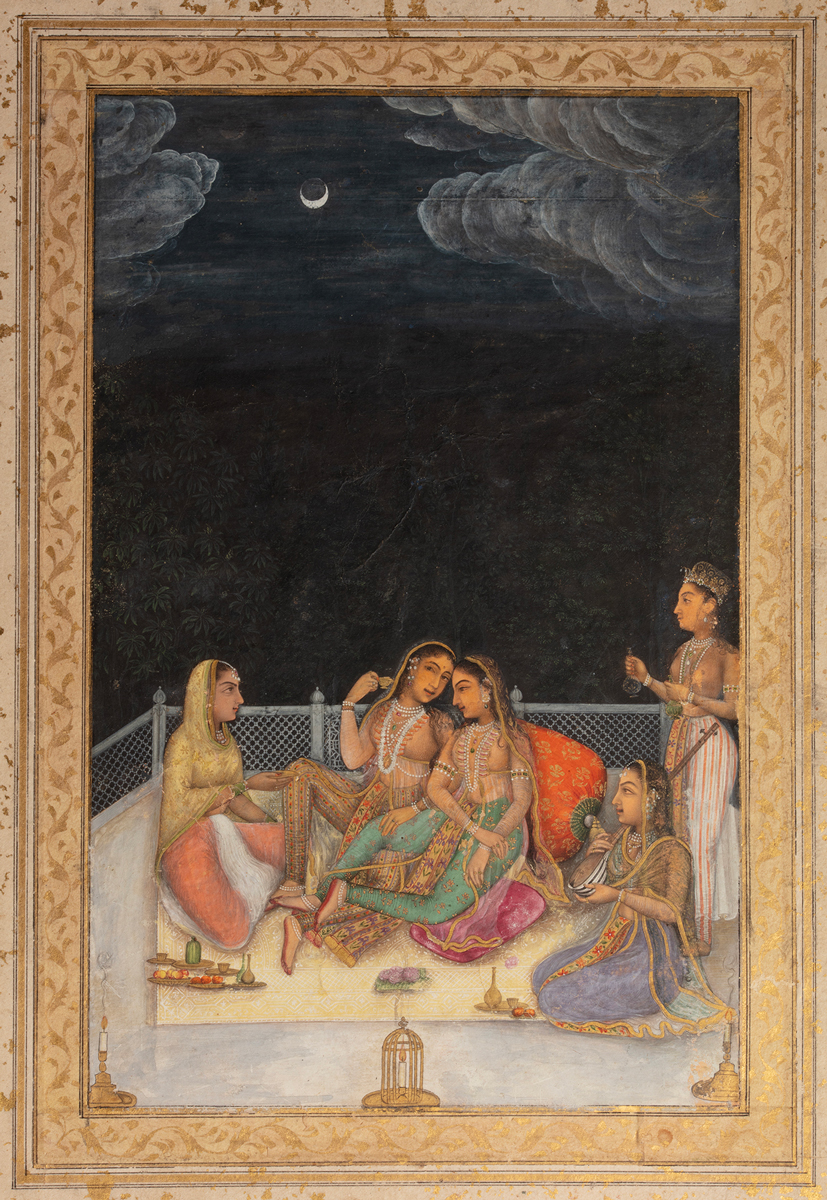

India’s Fascination with the Natural World

Mughal, Rajput and Company School Paintings

March 13 – 20, 2025

Exhibiting at: Les Enluminures Gallery, 23 East 73rd Street, 7th floor Penthouse

Asia Week Hours: 10am-6pm, dailly (otherwise by appointment)

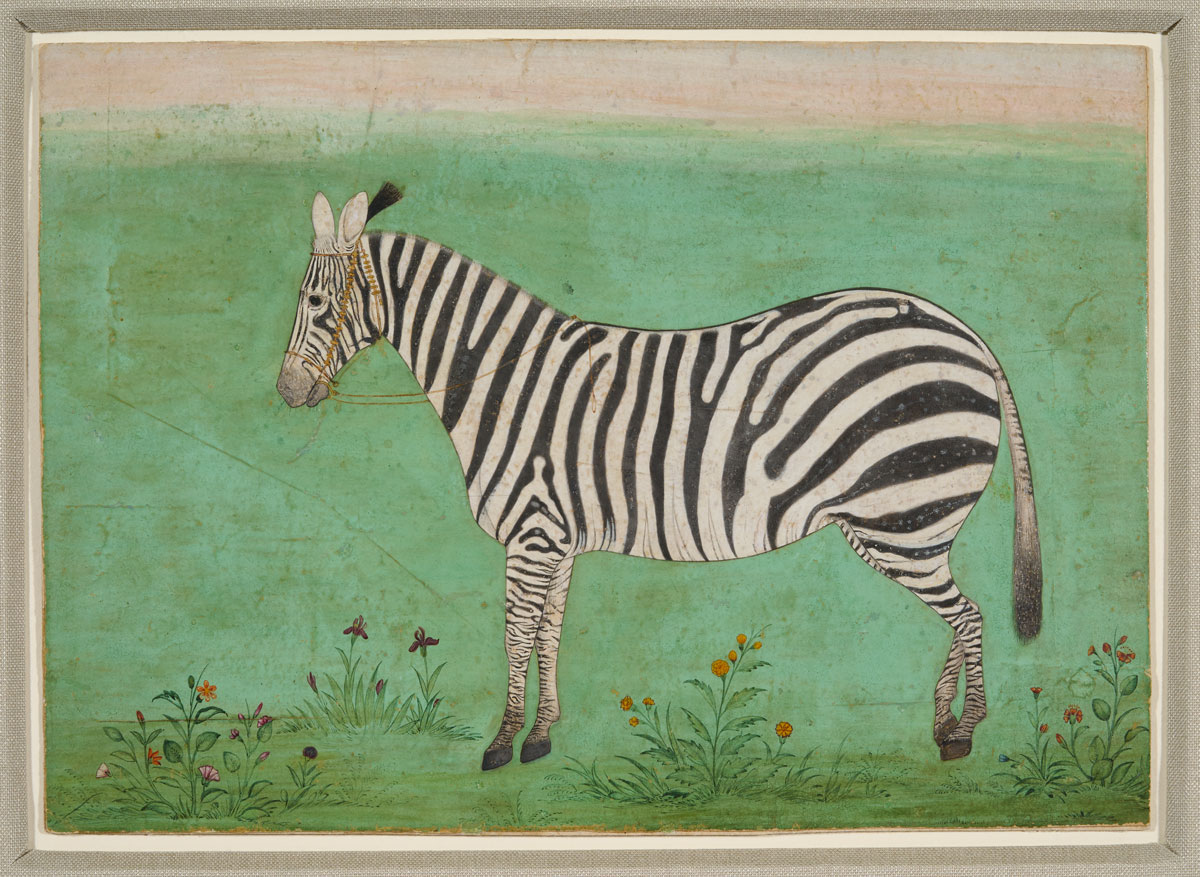

In 1621 a zebra from eastern Africa was presented to the emperor Jahangir, who had never seen an animal like this and thought his coat had been painted. But ‘after inspection it was clear that that was how God had made it’ (Jahangirnama -Memoirs of Jahangir Emperor of India). And so he had his master artist Mansur paint this zebra. This painting is currently on display in The Great Mughals exhibition at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London (Nov. 2024 – May 2025).

Our Mughal zebra, which we are proud to present at Asia Week, is of a similar date, but by a different hand. Such paintings are extremely rare and important, because they illustrate Imperial fascination with the wider natural world – animals that were not indigenous to India, like red squirrels, turkeys, ostriches and in our case a zebra.

A late 16th century Mughal portrait of a caparisoned horse with its three grooms, in spectacular condition, has a most unusual background, which evokes a Rothko painting. This miniature was once in the Imperial Mughal library, confirmed by numerous 17th century seals and inscriptions on the verso. The highly influential Mughal courtier, Asaf Khan,‘borrowed’ this painting during his lifetime. Of Persian origin, he became prime minister to Jahangir and later to Shah Jahan, and his daughter, Mumtaz Mahal, was the beloved wife of Shah Jahan who built the Taj Mahal in her memory.

India’s natural world also enchanted foreigners who spent time in this country. Foremost amongst these was Lady Impey who commissioned master artists, trained in the naturalistic Mughal tradition, to depict the animals in her Calcutta menagerie. In Indian art the Impey series of natural history drawings are considered the finest of their kind. Our notoriously cheerful and cheeky Lorikeet is from Lady Impey’s collection. The Rainbow Lorikeet are native to Australia but are also to be found in India.

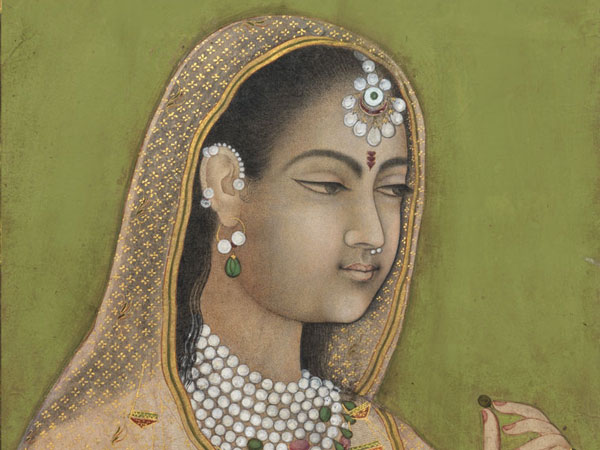

Our large, bust-length portrait of a beguiling Mughal Princess is by an unknown 18th century master. She holds a Phalsa (an Indian berry) between her left thumb and forefinger because it was to be consumed with wine, in the tiny blue and white porcelain cup she holds in her right hand – a delicious delicacy of the time.

To learn more and view our online catalog, click here.

About the Gallery

With forty years of experience and expertise, today Francesca Galloway is known as one of the foremost galleries dealing in Indian painting and courtly arts. Combining a personal approach with a global outlook, we regularly exhibit internationally. Collaborating with the leading scholars in this field, our catalogues and publications are reference works in their own right, helping to advance the research and visibility of this fascinating and important subject.