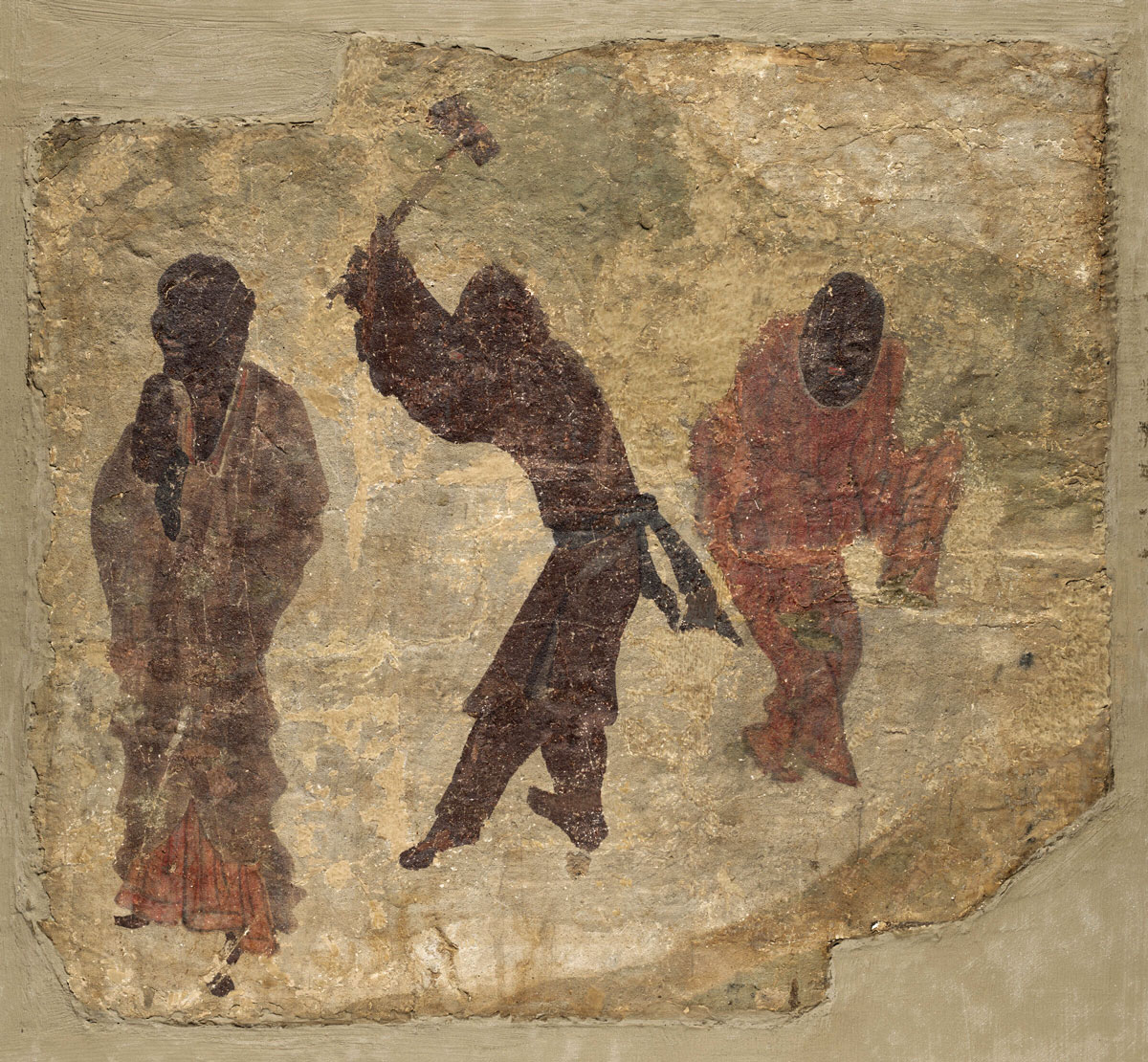

Three Figures (from the north side of the east wall of Mogao Cave 323, Dunhuang, Gansu province), Tang dynasty, 618-907, Section of a wall painting; polychromy on unfired clay; Harvard Art Museums/Arthur M. Sackler Museum, First Fogg Expedition to China (1923-1924)

The Art of Looking: 150 Years of Art History at Harvard

January 25 – May 11, 2025

University Teaching Gallery

“Hundreds of people can talk for one who can think, but thousands think for one who can see.” —John Ruskin

In 1874–75, the Harvard University course catalogue offered for the first time a series of electives in the history of art. These included two classes in the history of fine arts, taught by Charles Eliot Norton (1827–1908), and a drawing class, taught by Charles Herbert Moore (1840–1930). It marked the birth of the first art history department in the United States, a milestone in the formation of the discipline in this country. Norton believed that the appreciation of the fine arts demanded first to be educated in the art of looking and that learning to see was best accomplished through the practice of drawing. He laid the groundwork for a drawing program and pedagogy that centered students’ training on personal, hands-on interaction with art objects. As Fogg Museum director Edward W. Forbes (1873–1969) put it in 1911, the goal was to bring the “critical” and the “creative” into dialogue. “Art is not dead,” wrote Forbes, “it is not a memory of the past, nor a butterfly preserved in a glass bottle. It is among us, and is part of our life.”

In such a curriculum, the museum became a “laboratory” in which students were invited to encounter works of art as material artifacts, the result of human skill and technology—in other words, things and not only reproducible images or objects. The ideas laid out in these early years modeled the research and teaching of the Department of Fine Arts for more than half a century. Over time, these models would lead to an expanded curriculum that looked beyond the western canon as well as course subjects and museum collecting practices that would include contemporary art.

This installation, organized by Felipe Pereda, the Fernando Zóbel de Ayala Professor of Spanish Art, and the graduate students of his Methods and Theory of Art History seminar in Spring 2024, highlights a number of significant moments and central figures in the story of art history at Harvard.

The University Teaching Gallery serves faculty and students affiliated with Harvard’s Department of History of Art and Architecture. Small-scale, semester-long installations are mounted here in conjunction with undergraduate and graduate courses, supporting instruction in the critical analysis of art and making unique selections from the museums’ collections available to all visitors.

This installation is made possible in part by funding from the Gurel Student Exhibition Fund. Modern and contemporary art programs at the Harvard Art Museums are made possible in part by generous support from the Emily Rauh Pulitzer and Joseph Pulitzer, Jr., Fund for Modern and Contemporary Art.

To learn more, click here.

ONGOING EXHIBITIONS

Scaling Mountains

Through June 1, 2025

East Asian Galleries

The Mogao Cave Temples in Dunhuang

Ongoing

Later Buddhist Art Gallery

Uncovering the Library Cave

Through June 1, 2025

Later Buddhist Art Gallery

Gardens

Through November 2, 2025

Indian and Islamic Galleries

Installation view, Harvard Art Museums

The Collections

To view our collections from The Harvard Art Museums — the Fogg, Busch-Reisinger, and Arthur M. Sackler Museums, click here.